This blog was going to be called ‘The Hand of Buddha’, but, as so often, one thing led to another. The inspiration was found in the Chinese herbal garden at the Hortus in Leiden, which was in good autumnal form a few weeks ago (when it was still possible to travel through France and Belgium to the Netherlands, that is): Siebold, sardonic as ever, was pretending to ignore the blaze of Acer behind him, and the nerines were quite something too.

But I noticed for the first time (something to be said for going there in late autumn) a bizarre fruit on several small citrus trees, not the globe or oval of a normal orange or lemon, but with several ‘fingers’ curling upwards from the stalk. This is the Citrus medica var. sarcodactylis (I think, see below), the so-called ‘Hand of Buddha’ fruit, or fingered citron. It comes from an area ranging from north-eastern India to China, and usually contains little or no pulp, but is highly scented. The zest can be used for flavouring drinks, or candied in cooking, while the whole fruit is used to scent rooms or store among clothes as one would a lavender bag.

The taxonomy is sufficiently complicated that I don’t understand it and will not attempt to reproduce it. The name given above (not confirmed by IPNI, however) is explicated ‘Siebold (ex Hoola van Nooten) Swingle’. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if Siebold was involved, but who are Hoola van Nooten and Swingle?

Berthe Hoola van Nooten (1817–92), born in Utrecht, married in 1838 a judge whose district was Paramaribo in the Dutch colony of Suriname. Already interested in botany, she collected specimens on her travels with her husband, sending them back to botanic gardens in the Netherlands. They later moved to the United States and opened a (Protestant) school for girls, but in 1847 her husband died of yellow fever; the school survived and moved to first to Louisiana and then to Texas, but Berthe had money problems, and seems to have left the US to travel with her brother, a sugar merchant, to Java, where she set up another school, and met a Javanese botanical artist, Radhen Salikin, who helped familiarise her with the local flora. This resulted in in a book, Fleurs, Fruits et Feuillages, choisis de l’île Java: peints d’après nature, containing 40 coloured plates from paintings by her, which was published in Brussels in 1863 and dedicated to Queen Sophie Mathilde of the Netherlands. Sadly, although the book was a success and went into several editions, Berthe died in poverty in Jakarta in 1892.

Walter Tennyson Swingle (1871–1952), by comparison, has a conventional botanical background in the United States (though he studied in Germany in 1895–6). Working for the US Department of Agriculture, he became an expert on the commercial cultivation of all types of citrus, identifying many new varieties, and introducing many new types to the US, and was the acknowledged world expert in this field: read more in the Florida Citrus Hall of Fame.

So I’m assuming that Siebold put the Hand of Buddha in the class of Citrus medica (Linnaeus 1753), that Hoola van Nooten called it Citrus sarcodactylis (= ‘fleshy fingers’, as in her plate, below), and that Swingle classed sarcodactylis as a variety of C. medica, but this is my guesswork.

Anyway, searching for illustrations for this piece, I came across Johann Christoph Volkamer (1644–1720), merchant and botanist of Nuremberg, who produced the Nuremberg Hesperides, a two-volume work on citrus fruits (and much more) in 1708 and 1714 (and started a third volume, which was never completed). In the 1660s, Volkamer was managing a silk factory that his grandfather had established in Rovereto in northern Italy, but he then returned to Nuremberg, where he dedicated himself to the cultivation and study of citrus in his garden in the suburb of Gostenhof.

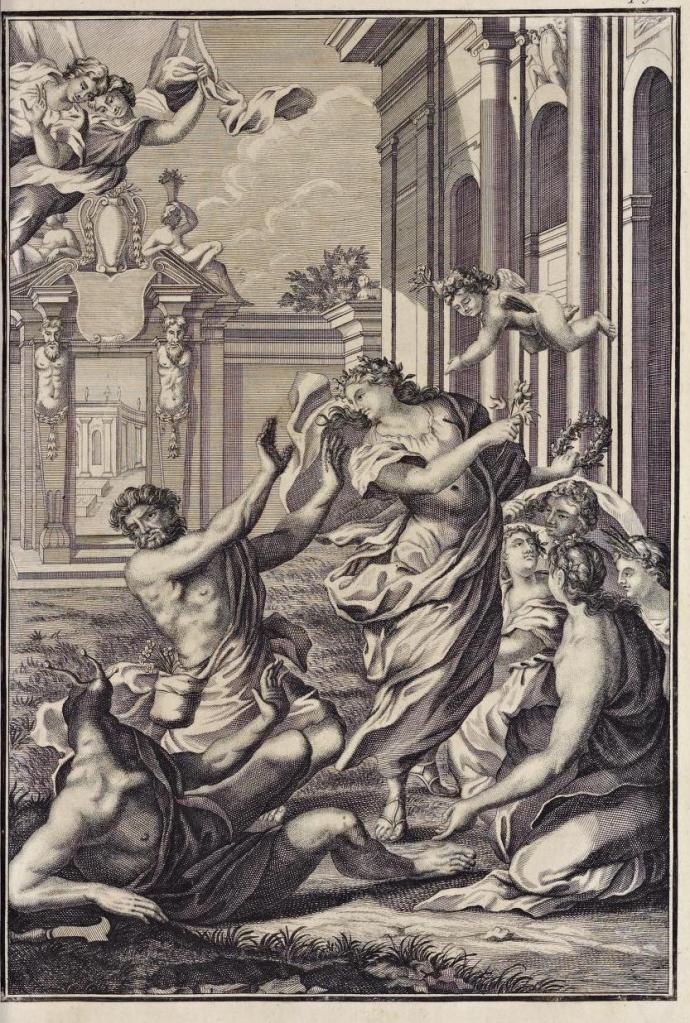

He may have been inspired by an earlier work by Giovanni Battista Ferrari (1584–1655) a Jesuit and expert in Oriental languages who was also the gardener to Cardinal Francesco Barberini in Rome, and who wrote a De florum cultura, and Hesperides, sive de Malorum Aureorum Cultura et Usu Libri Quatuor (1646), a monumental folio volume containing 115 plates ‘on the culture and use of golden apples’, i.e. citrus fruit, the Golden Apples of the Hesperides – if, of course, these were not pomegranates.

Ferrari was almost certainly influenced in this work by Cardinal Barberini’s polymathic secretary, Cassiano dal Pozzo (1588–1657), who was apparently very interested in citrus, and collected everything from paintings and drawings by his contemporaries (he was a great friend of Poussin) to antiquities, fossils, geological samples and botanical prints and drawings – which after his death passed to Pope Clement XI, then to his nephew Cardinal Alessandro Albani. Then the bulk of the collection was purchased in 1762 for George III of Great Britain, and remains part of the Royal Collection, though, depending on the objects, it is spread between Windsor Castle, the British Library, the British Museum and Kew Gardens: a project is under way to catalogue the entire collection, something which dal Pozzo never quite succeeded in doing.

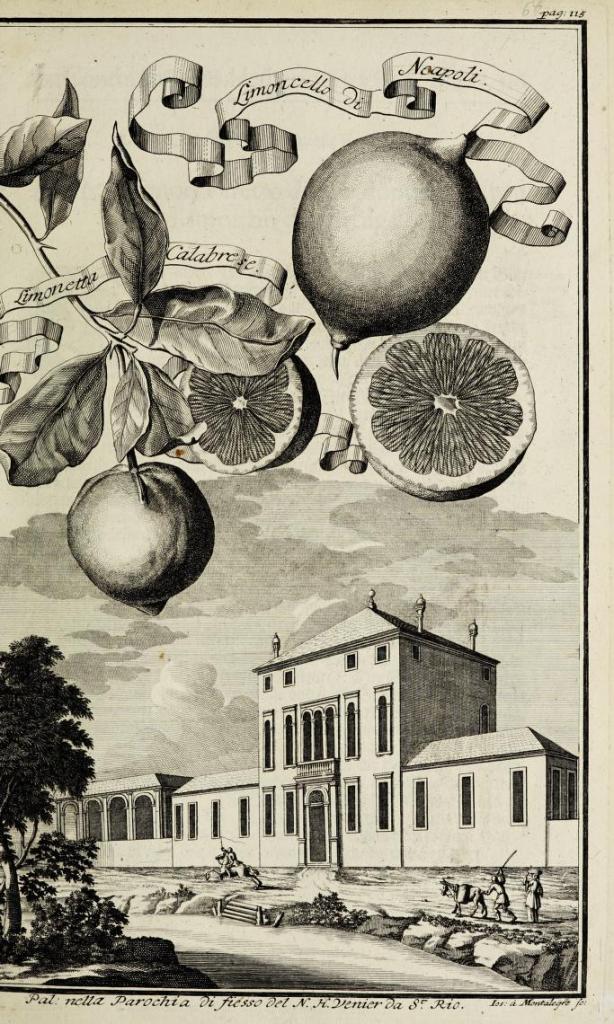

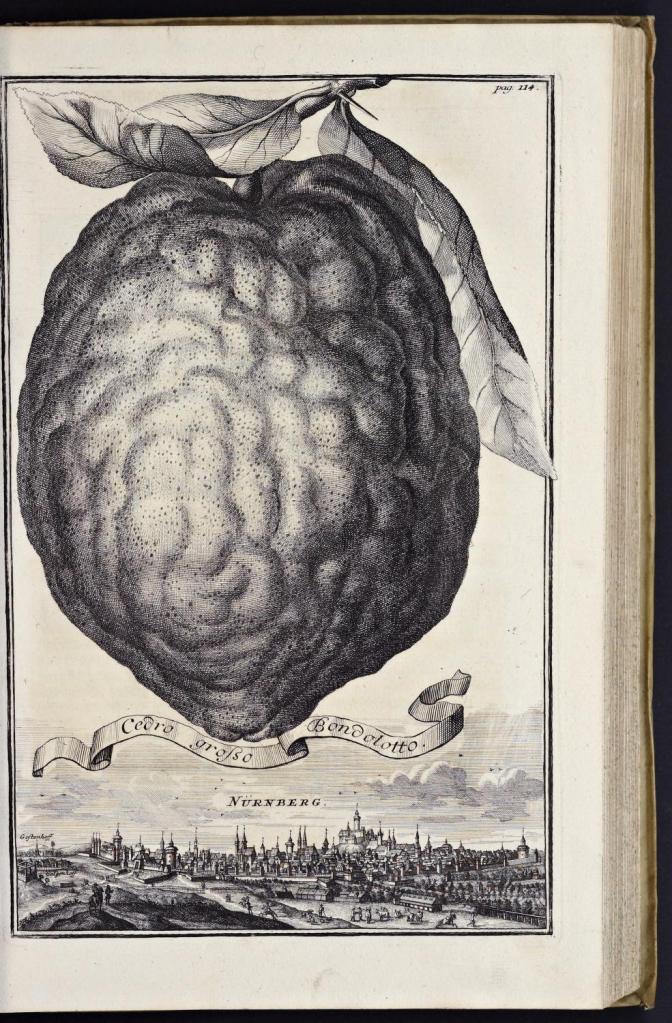

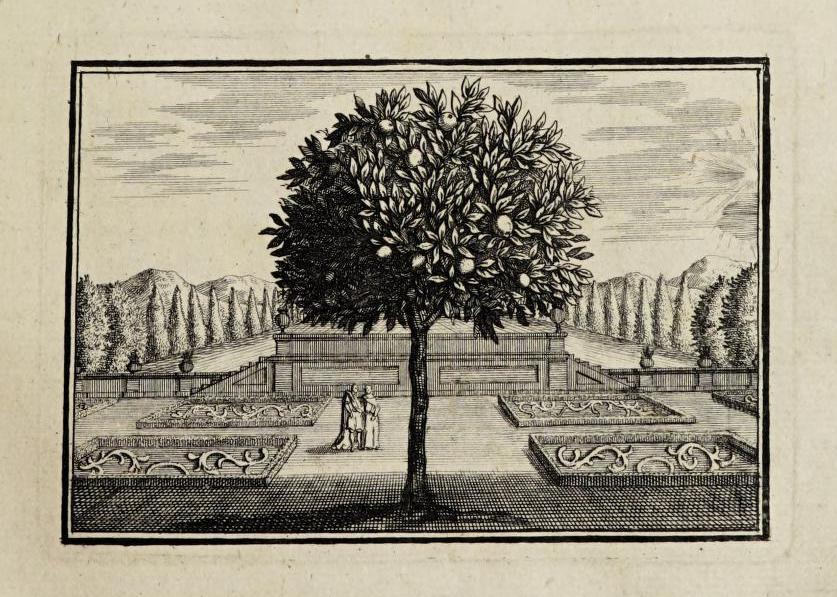

At a time when improving glass technology was enabling glasshouses and orangeries in northern Europe, and getting citrus to flower and fruit for you was a huge mark of status (cf. pineapples), it is perhaps not surprising that, in the wealthy city of Nuremberg, Volkamer decided to produce his own version of the Hesperides. What makes it unusual, however, is that the illustrations of the individual varieties of fruit are combined with views of Nuremberg itself, its surrounding villages, palaces such as Schönbrunn outside Vienna, and other famous gardens in Europe, notably those of Padua, Verona and the country villas of the Venetian aristocracy along the Brenta Canal and in the Euganean Hills, with which we assume that Volkamer had become familiar during his years of working in Italy.

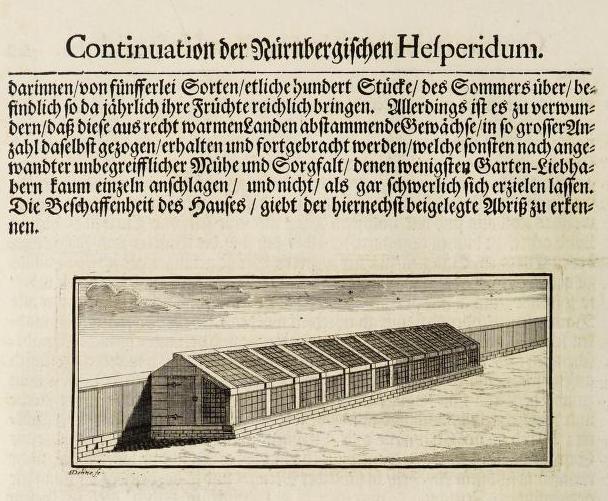

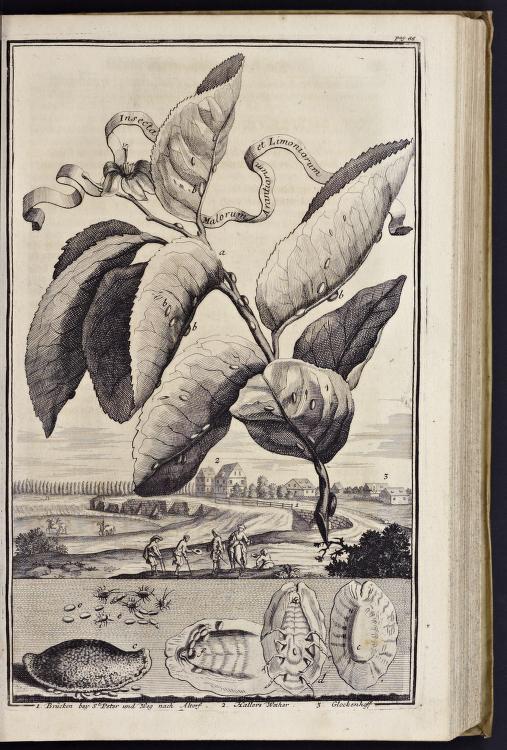

He also provides garden layouts and diagrams of glasshouses, and more plates showing both natives such as primroses (in a section called ‘The Flora of Nuremberg’), and also exotic plants in their native habitats, such as a Dracaena at the Cape of Good Hope, or a date palm at Nazareth – plants which he had apparently purchased and had shipped back to him.

The German publisher Taschen has recently issued a coloured version of the plates (drawn from a coloured set in the municipal archive of Fürth, near Nuremberg, and including some made for the planned but never published third volume), but if you don’t have £125 to spare, you can see the two full volumes in black and white at the Biodiversity Heritage Library (Vol. 1 here and Vol. 2 here).

Volume 1 is perhaps more practical: one of the illustrations (above, with a background landscape showing (if I decipher correctly) ‘the bridge by St Peter’s at Altorf, Hallers works (???) and the bell-house)’, depicts various pests of citrus – ‘Insecta Malorum Arantiarum et Limoniarum’ – and the damage they do to the leaves. It also has attractive tail-pieces:

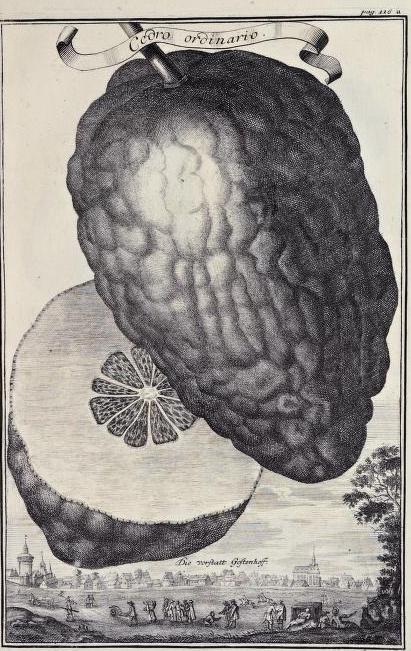

but I think the really spectacular plates are in Volume 2, where the engraving team of Decker, Glotsch, Steinberger, Pfann, Montalegre, Beckh, Dehne, Delsenbach, Böllmann, Lindner and Krieger have laboured mightily to produce lifesize images of the fruits floating above various locations, including the country homes of the Venier, Contarini, Priuli, Pisani, Bembo, Grimani and others in the Veneto countryside. (It is interesting that the names of the various fruits are invariably in Italian.)

Of the names of the many and varied fruits (impossible to know now how many distinct varieties (in modern terms) there actually were), some are derived from the places in which they were thought to have originated: Limea Romana, Limonzin da Portugal, Cedro da Sina (China), Limon bizantino, Limon da Calabria, Limon da Neapoli, Aranzo da Candia (Heraklion in Crete), Cedrato da Garda and many others. Among descriptive terms, ‘monstroso’ appears quite often to describe bizarre forms, as does ‘verrucosa’ (warty) while others are ‘di fior doppio’ (double-flowered), or red- or pink-flowered, or variegated. Some names give an indication of the taste: ‘di sugo dolce’ (sweet sauce), ‘agra’ (sour) or ‘acida’ (acidic); while one lemon is described simply as ‘incomparabile’.

I wish my German were good enough to read Volkamer’s fascinating and beautiful work with proper understanding – what on earth, for example, is going on here? –

but there are many rather more significant improvements that we can all wish for in 2022. May they all appear!

Caroline

A very detailed explanation of such a differe nt world to ours where we are so blasé about fruits! The green hand of the Buddha is so strange – no wonder it has such a name. It reminded me somehow of Ghost Wort! Or Dead man’s Fingers! Totally other of course. Intrigued that one engraver was called Decker. A possible ancestor of our Matthew??

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I agree about dead man’s fingers! The Decker name idea is interesting: I need to find out how common a name it was at the period, and whether anything more is known about the individual engravers.

LikeLike

Well the fact that MD was so interested in growing a pineapple from seed may link back to an ancestor who was involved in this study. Clearly to them this was a form of scientific research. We have always taken his achievement as merely a hobby of a wealthy man but maybe cultivating the pineapple had deeper family roots?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Caroline, what a nice and interesting article you have written about the Hand of Buddha, thanks so much! I myself am currently writing a complete biography of Berthe Hoola van Nooten (almost finished), and already published several articles on her and her work on my blog, Magazijn van Natuurlijk history (https://davidcoppoolse.com/) – is it possible you read some of these, and tried to translate them (they are in Dutch, of course…)? If so, please feel free to ask me anything on Berthe and her work….best regards! David

LikeLike

Dear David, thank you for your kind comments, and for the link to your blog. My Dutch is virtually non-existent, so I have not come across your work, but I have a close friend who is Dutch and therefore bilingual, and I will ask for her help. Good luck with your book, and please try to find an English publisher for it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Caroline, thanks so much for your quick and kind reply! I wil certainly try to find an English publisher, and will then inform you…best regards, David

LikeLiked by 1 person

(If your friend really wants to read something about Berthe’s Hand of Buddha, this is my article: https://davidcoppoolse.com/2012/10/29/de-hand-van-boeddha-berthe-hoola-van-nooten-en-haar-javaanse-vingercitroen/)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks: even if she doesn’t want to, I’ll get her to translate for me!

LikeLike

Pingback: Another Botanic Garden | Professor Hedgehog's Journal