Some of the most ancient artefacts which have survived to grace our modern museums were carved from bone or ivory: hardwearing substances, which survive almost anything except a severe conflagration or a deliberate act of grinding them to shards or powder. The earliest known worked ivory consists of beads made from mammoth tusks, found in the area of Baden-Württemberg in Germany and in various cave sites in France, and figurines from the same caves have been dated to 35,000–30,000 BP.

Some of the most ancient artefacts which have survived to grace our modern museums were carved from bone or ivory: hardwearing substances, which survive almost anything except a severe conflagration or a deliberate act of grinding them to shards or powder. The earliest known worked ivory consists of beads made from mammoth tusks, found in the area of Baden-Württemberg in Germany and in various cave sites in France, and figurines from the same caves have been dated to 35,000–30,000 BP.

The famous Upper Palaeolithic site of Dolni Vestonice contained mammoth ivory representations of female heads, and most civilisations which have had access to the raw material, whether from mammoth or elephant tusks, rhinoceros or narwhal horns, have prized it (I quote) ‘for its malleability in working it into shapes, as well as its density, fineness of grain, lustre when polished, weight and warmth of texture’.

Head of a woman, from Dolni Vestonice.

The definition of ivory (from the same helpful website) is: ‘a natural, osseous raw material, that is part of the dentition of a wide variety of animals … a rigid biological composite, made of a matrix buttressed by a crystalline lattice of hydroxyapetite, a calcium phosphate which makes up most human and animal bone’. In European history, elephant tusks have been used to create legendary works of art: Phidias’s chryselephantine statue of Zeus at Olympia (43 feet tall, a wooden frame clad in ivory and gold of the king of the gods on his throne), or the same sculptor’s Athene Parthenos in the Parthenon in Athens. Some damaged fragments of similar work have survived to give a notion of what the gigantic deities would have looked like.

A burnt ivory figure and remains of gold decoration, from the Delphi Archaeological Museum.

In the medieval and Byzantine periods, ivory was carved superbly to decorate boxes and chests, and whole tusks were sometimes used to create statues of the Virgin and Child, the curve of the tusk facilitating the protective, slightly bent stance of the mother. The trade routes and exchange procedures to obtain this most desirable and expensive of materials – whether from Africa or from India – must have been tortuous.

A thirteenth-century Madonna and child in the Louvre Museum, Paris.

However, this month’s objects are at a less exalted level and of a considerably later date. The scrimshaw on display at the Scott Polar Museum in Cambridge dates from the 1750s through to the period of the end of commercial whaling, and provides fascinating information on the way that early whalers and other sailors passed their time. Carving or whittling on bone or ivory was a well known hobby on board ship, and the products could be sold in port to augment one’s income. There are many examples from the excavations at Portchester Castle in Hampshire, and other sites used for prisoners of war during the Napoleonic period, of (mostly) sheep bones with whittle marks on them, so say nothing of superb rigged ships and other toys which the bored and confined French made to sell to curious visitors.

This model ship (‘Le Vengeur du Peuple’, of which the original was sunk on the Glorious First of June) was made at Portchester Castle and is now in the Vancouver Maritime Museum, Canada.

A model of a guillotine made of animal bones, c. 1800–15.

But scrimshaw (of which the etymology is not known) is more specific than modelling or sculpting in bone or ivory: according to the somewhat chauvinistic Merriam-Webster’s dictionary, it is ‘any of various carved or engraved articles made originally by American whalers usually from baleen or whale ivory’, and was first used about 1826. However, the more generally accepted definition limits the word to describe any whale or walrus ivory or baleen with superficial engraving, the lines usually darkened with black (or occasionally polychrome) pigment, but with the tooth or tusk maintaining its original shape.

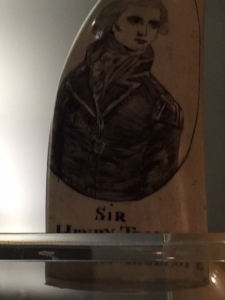

The inspiration for some of these teeth seems to have been prints. Instantly recognisable is a version of David’s ‘Napoleon Crossing the Alps’, and another ‘real’ figure is Admiral Sir Henry Trollope.

Napoleon in scrimshaw.

David’s famous original.

Admiral Sir Henry Trollope (1756–1839). His likeness may have been taken from the Naval Chronicle.

There is a rare Spanish specimen showing Hercules on one side, carrying the skin of the Nemean lion and with his foot on the head of the hind of Ceryneia, while on the reverse appears the personification of Liberty with her cap.

The Spanish Hercules.

The personification of Liberty sits by an altar.

A Highland soldier and (perhaps) the humble croft that was his home appear on another; there is an American eagle, St George slaying the dragon, two- and three-masted ships, and some birds on their nests.

A Scots soldier below a cottage.

A ship, with detailed rigging.

An American eagle.

Birds in their nests.

St George with rather a small dragon.

Most remarkable, however, are the well-dressed ladies, perhaps taken from fashion plates rather than direct observation. The style of dress helps to date the images: there is a girl in a simple, high-waisted costume with plainly dressed hair who could have been a Jane Austen heroine.

A Jane Austen lady.

A lady with elaborate ringlets, bulging sleeves and a hat ornament with enormous bows and feathers can be matched to this 1836 portrait of Queen Adelaide, consort of William IV, by Sir Martin Archer-Shee, President of the Royal Academy.

The more elaborate costume of the 1830s.

Queen Adelaide, with hugely puffed sleeves and feathered hat.

A mid-Victorian lady with a plaid shawl and holding a book could be one of Trollope’s more thoughtful heroines.

A woman in mid-Victorian dress with a plaid shawl, holding a book.

There is information (and much better pictures than mine!) on all these images and more on the Scott Polar Museum website. It is suggested that most scrimshaw was produced on whaling vessels: not only did the crews have access to the raw material, but also long periods of leisure time on their way to and from the whaling grounds of the northern and southern hemispheres.

Apparently, scrimshaw is still produced by ‘scrimshanders’, whose chief difficulty must be in obtaining the raw material: the various legal restrictions on the sale of modern elephant, whale and walrus ivory mean that they have to rely on ‘antique’ tusks and teeth appearing in sales. But what was the motive of the hobbyists in the lower decks of a desperately uncomfortable whaling ship? Gifts for sweethearts, craftwork for sale, or just a way of passing time and distracting oneself from days of sea-tossed monotony intersected with sudden and serious danger?

Caroline

Pingback: Object Of The Month: September | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Object of the Month: August 2018 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal