When I was unexpectedly cast upon the shore of the Island of Leisure, nearly three years ago now, one of the resolutions I made to myself in contemplation of the Rest of the Journey of My Life was that I would not leave seeing any exhibition until the last few, crowded, hurried, sweaty (yes, Mr Hokusai, I’m thinking of you) days of its existence. Behold me then, arriving at the British Museum 10.30 a.m. on 11 January, to see the exhibition of a very small number of items, relating to his medical interests, from Sir Hans Sloane’s monumental collection. This small show in the Print Rooms had opened at some time in the autumn (I can’t find when, as all mention of it seems to have been struck from the web), and closed precisely on 11 January 2018 (possibly not coincidentally the anniversary of Sloane’s death in 1753). However, I didn’t need to worry about crowds, which made a nice change …

When I was unexpectedly cast upon the shore of the Island of Leisure, nearly three years ago now, one of the resolutions I made to myself in contemplation of the Rest of the Journey of My Life was that I would not leave seeing any exhibition until the last few, crowded, hurried, sweaty (yes, Mr Hokusai, I’m thinking of you) days of its existence. Behold me then, arriving at the British Museum 10.30 a.m. on 11 January, to see the exhibition of a very small number of items, relating to his medical interests, from Sir Hans Sloane’s monumental collection. This small show in the Print Rooms had opened at some time in the autumn (I can’t find when, as all mention of it seems to have been struck from the web), and closed precisely on 11 January 2018 (possibly not coincidentally the anniversary of Sloane’s death in 1753). However, I didn’t need to worry about crowds, which made a nice change …

I have in fact simultaneously got ahead of myself on the subject of Sloane, because I haven’t yet started (from my Birthday/Christmas pile) James Delbourgo’s Collecting the World: The Life and Curiosity of Hans Sloane (I’m on Jenny Uglow’s wonderful Mr Lear at the moment, since you ask), but as anyone who follows this blog may readily discover, knowing nothing about my subject has never prevented me offering my tuppence-worth, so here we go.

This extraordinary watercolour of an orang-utan was painted in the 1730s by for Sloane by George Edwards (1694–1773). Its subject had been dissected in 1698, and had been preserved in this anthropomorphic pose.

The enormous size of Sloane’s collection, its significance as Stuff, and the insights it may offer into the intellectual and scientific mindset of the man and his times have inevitably been rather obscured by the gradual splitting up of the material: the foundation of the Natural History Museum led to the ‘scientific’ collections being moved (in the same way as happened with Sir Joseph Banks’ herbarium and library), and later, with the fissuring off of the British Library, printed and manuscript material was relocated. However, there is an ambitious and terrific-sounding project under way ‘which eventually aims to digitize and catalogue his collections across the three institutions and even further and to identify and link Sloane’s networks of contacts, in order to help us understand how knowledge was formed and exchanged through objects in the early modern world and the implications this has for us today’.

A trompe-l’oeil ‘medley’ from the collection, a pen and ink drawing by Bernard Lens II (1695–1725), with William III surrounded by emblems of his day.

Sloane was born at Killyleagh in Ireland, the seventh son of Alexander (was he too a seventh son?), whose family had originally settled in the country as part of James I’s ‘Plantation’ of Scots families in the island. His own inclination for scientific study seems to have directed him towards medicine, but his education was set back by three years by a severe illness at the age of sixteen. At nineteen he was in London, living close to Apothecaries’ Hall and studying chemistry; presumably he also made use of the Physic Garden. He also became acquainted with John Ray and Robert Boyle (and hence, again presumably, with the intellectual elite of the city).

Sloane owned this chalk drawing of John Ray by William Faithorn (executed between 1670 and 1690).

He continued his medical studies in Paris, the University of Orange (where as a Protestant he could take his doctorate) and Montpellier, where he was recommended to the medical faculty by Tournefort, and worked with the botanist Pierre Magnol (cf. the Magnolia family), before returning to England in 1687.

Pierre Magnol, not a completely flattering image. By coincidence (of which there is no such thing), it was Charles Plumier who first used the eponym ‘Magnolia’ for a flowering tree – see the image of Plumeria below.

He stayed for barely six months before agreeing to become personal physician to the second duke of Albemarle, which entailed relocating to Jamaica, whither the duke was going as governor.

On the island, he made the most of every opportunity to study all aspects of natural history, especially the curative properties of plants, but the stay was brought short within a year by the untimely death of his patron, and he returned to London with the latter’s embalmed body, a huge collection of natural history specimens, and the notes for his first publications. And the rest is biography …

The title page of Sloane’s Voyage of 1707. Many of his discoveries were published as papers in the Transactions of the Royal Society.

The little BM exhibition opened with an mezzotint engraving by John Faber the Younger (1684–1756) of Sloane, derived from the Godfrey Kneller portrait which Sloane himself commissioned and presented to the Royal Society in 1716.

Faber’s engraving of the Kneller portrait of 1716.

Among the most beautiful items on the show are two botanical paintings by the great Maria Sibylla Merian, and a splendid ibis (albeit unauthentically eating a snake) by her daughter Dorothea Graff (1678–1743).

Passiflora (above) and Plumeria (below), by Maria Sibylla Merian.

Watercolour of an ibis, by Dorothea Graff (c. 1700–7).

There are also two studies of poppies by Jan Van Huysum, best known for his spectacular still-life assemblages of all sorts of flowers, in and out of season, together.

A characteristic flower painting by Jan Van Huysum. (Credit: the Fitzwilliam Museum)

These watercolours, by contrast, are almost ‘botanical’ in their detail, and the texture of the petals is magical.

Two watercolours of poppies by Jan Van Huysum.

One of the more bizarre objects is a spoon, carved from the breastbone of a great auk, with its origins inscribed on its surface: the spoon had been made a by a Native American woman, and sent to Sloane by John Winthrop, scientist grandson of the more famous, and enthusiastic collector, who Sloane proposed as a member of the Royal Society in 1733. (By the way, Benjamin Franklin sold Sloane an asbestos purse for his mineral collection …)

Other curiosities include a Chinese tortoiseshell ear-cleaner, and a print showing a bunch of grapes with a beard.

‘Accurate view of a bunch of grapes with a triple beard like hair’, by Jakob von der Heyden (1615).

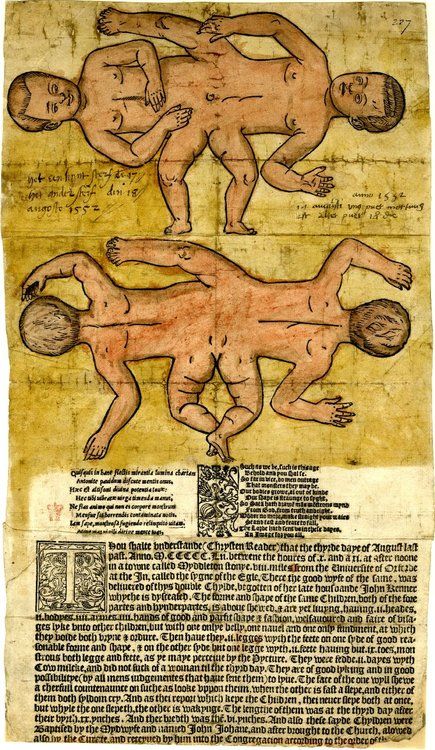

More specific to the medical side of Sloane’s life are prints concerned with ‘monstrous’ births, of conjoined twins. A broadside of 1552 describes how twins were born (after the death of their father, the sort of trauma which was believed to give rise to prodigies) on 3 August to the landlady of the Eagle Inn at Middleton Stoney in Oxfordshire: ‘these said children were baptised by the midwife John Johan, and after brought to the church, allowed by the curate, and received by him into the congregation’.

This is thought to be the first record of a conjoined birth in England, and the touching details about the children are – surprisingly and thankfully – a long way from the reaction of alarm or horror that might have been expected at the period. One wonders what happened next: baptism and burial records for the village exist only from 1598, and the Eagle Inn is not there any more, though of course the church is. Unimaginable that they could have survived, but at least they were welcomed into the world and the community.

The church of All Saints at Middleton Stoney, Oxfordshire.

Perhaps the most important item in the exhibition is a (very) small extract from Sloane’s own numbered descriptions of his collection. He compiled forty catalogues, the one named ‘Miscellanies’ alone containing over 3,000 entries. As well as measurements, a verbal description and a note on provenance, he often described what the item was for (as well as Van Huysum’s poppy paintings, he had acquired ‘A poppy head from Smyrna cut by the Turks to yield the milk which is received on a poppy leaf and is condensed into opium’), and occasionally added a little outline drawing. His own meticulous records are presumably the basis of the ‘Sloane’s Treasures’ project, for which this tiny but fascinating exhibition was an exciting forerunner.

Caroline

P.S. I’ve just noticed that this is my 200th blog: if you have been, thanks for being with me.

Congratulations on 200th blog. May there be many more- they have given me so much pleasure!

LikeLike

Dear Lisa, thanks so much for your kind words – it’s really lovely to receive such a response!

LikeLike

Pingback: Mr and Miss Morris | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Plant of the Month: March 2018 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: When It’s Gone, It’s Gone … | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Fool’s Gold | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Paston Treasure | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Plant of the Month: March 2019 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Sedgwick’s Boots | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Francesco Cupani | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Eight Wonders of the World | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Plant of the Month: November 2020 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Mr Kick and Mr Frankcom | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Plant of the Month: August 2021 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal