On 21 January, already deeply memorable as a family birthday, I was looking for a picture of a squirrel, since some Power had Decreed that it was also Squirrel Appreciation Day. The photo I found was a rather bad (full of glass reflections) one I completely forgot I had taken, two years ago: on that occasion I wrote instead about a German tankard from the Glaisher bequest with deer on it.

On 21 January, already deeply memorable as a family birthday, I was looking for a picture of a squirrel, since some Power had Decreed that it was also Squirrel Appreciation Day. The photo I found was a rather bad (full of glass reflections) one I completely forgot I had taken, two years ago: on that occasion I wrote instead about a German tankard from the Glaisher bequest with deer on it.

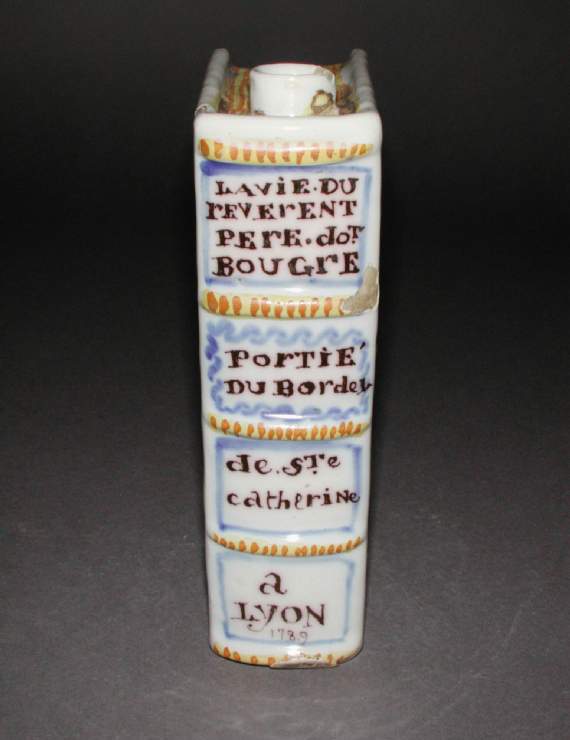

When I went to revisit him a few days ago, the industrious squirrel on his ‘book flask’ was no longer in place, replaced by other examples of early modern European ceramics. But of course you can get a good view of him on the Fitzwilliam Museum website, where you can also see the other side of the flask, where rabbits are caught up in dubious activity, and the side which forms the ‘spine’ of the book, which somewhat echoes the rabbits in its references to sexual shenanigans (in French).

The wool-winding squirrel from Lyons, 1789. (Credit: the Fitzwilliam Museum)

The spine of the flask.

Book-shaped flasks are not uncommon, though they were not necessarily containers for drink: this little stoneware ‘book’ with elaborate stamped binding and three spine-bands (another Glaisher item) is thought to have been a hand-warmer, perhaps for use in a chilly church, where it might match your prayer-book?

Stoneware flask in the form of an elaborately stamped, leather-bound book.

Another, in Delft ware and from the Netherlands, though the factory is unknown, is dated 1709. The moulding gives not only four spine bands, but also two clasps at the fore-edge, though the decoration is a bit splodgy, neither convincingly figurative, nor abstract enough to suggest marbling or another patterned finish.

A Delft-ware flask with spine bands and clasps.

However, our squirrel flask seems to be the only one actually used to contain drink (as opposed to hot water), judging by the cork-sized opening at the top.

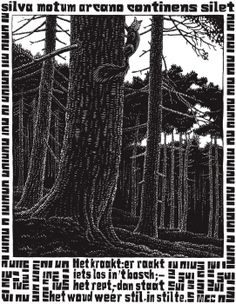

But what do we make of the squirrel’s yarn-winding activity, especially by contrast with the salacious suggestiveness of the other side and the spine? Is the squirrel an emblem of bawdy or suggestive activity? When I googled ‘emblemata squirrel’, hoping to find what the beast stood for in the seventeenth-century Dutch (as opposed to the eighteenth-century French) mind, I was surprised that the first hit was an engraving by M.C. Escher (he of the vertiginous staircases going nowhere), of which the Latin text means (presumably?) ‘the secret wood, though containing motion, remains silent’, and the Dutch (thanks, Dr S.!): ‘It’s creaking, something is coming loose in the wood; it speaks; then the wood stands still in silence again.’

The squirrel in the wood, one of a series of emblemata created by M.C. Escher (1898–1972) in 1931. (Credit: The M.C. Escher Foundation)

But, more helpfully, I also found a link to a book I’ve got, the gorgeous London’s Lost Jewels, where Hazel Forsyth, writing about the cornelian pendant of a squirrel found in the Cheapside Hoard, notes: ‘Some depictions of squirrels were amatory, even erotic, in intent. In Emblemata amatoria, for example, Pieter Cornelisz shows a cherub gazing at a squirrel in a wheel with the supporting motto More rotam inclusi volvo atque revolve sciuri. Fine carens captum circuluis urget: amo. (Like a caged squirrel I turn the wheel and turn it again. A circle without end pushes me on, trapped: I am in love.)

On the flask, of course, the squirrel is outside the wheel, forcing the pace of its revolutions – a table-turning, or a sort of lover’s revenge? The most common image of the squirrel in the emblem-books appears to be the illustration to the motto ‘Vincit sollertia vires’, ‘Wit is better than strength’, where a squirrel makes a boat out of a floating piece of wood and spreads its tail to act as a sail.

The squirrel as emblem for ingenuity, by Gabriel Rollenhagen (1583–1619).

Another nautical squirrel, by the French writer and publisher Gilles Corrozet (1510–68).

The squirrel as an example of self-help, in Sinnepoppen, by the great Dutch emblem-maker Roemer Visscher (1547–1620).

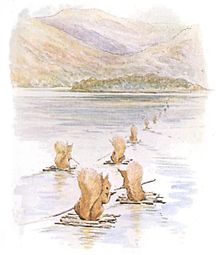

(Beatrix Potter of course took up the same motif in The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin.)

Beatrix Potter’s take on squirrel ingenuity.

Another, also by Rollenhagen, has the squirrel as the emblem of endurance, crouching on a log in a rainstorm with its tail spread over its back, waiting for the sun to come out.

Rollenhagen’s squirrel in rain, waiting for the sun to come out.

(Though in my own experience – of grey squirrels only, admittedly – they are very reluctant to get wet, as water clinging to their fur adds considerably to their body weight, and I believe they drown very easily.)

None of this gets us any closer to understanding the significance of the squirrel and the yarnwinder, or ‘swift’. I mentioned before that the swift is a quite elaborate example of the truism that once any tool shape is discovered to be effective, it doesn’t change: you can still buy an almost identical one.

A nineteenth-century yarnwinder or swift.

A modern table-top swift.

These days, most yarn is bought already balled, but it used to come in skeins – and still sometimes does so if you are buying high-end, gorgeous-coloured, drool-engendering, artisanal stuff, which you then have to wind into balls yourself before you can start knitting.

I was brought up to believe that this was what the arms of young girls were made for, and I usually make do (if Him Indoors is not available to be bludgeoned into service) with my own knees or the back of a chair. (I find Max the Cat sadly uncooperative on these occasions.) But if you have masses of skeins to ball up, then the swift and your own hands are clearly the solution. (There is also the possibility of the pared-down Shaker version, or a hugely more up-to-date but aesthetically non-starting plastic baller.)

A Shaker-type swift, much simpler than the ‘umbrella’ type above.

The rather less attractive, if very efficient, modern version.

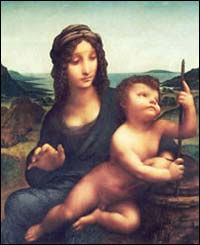

There is of course another type of yardwinder, held by the Madonna in at least two paintings at least partly by the hand of Leonardo da Vinci (note the caution there!), the Buccleuch Madonna and the Lansdowne Madonna (the former has a remarkable and recent theft-and-recovery story attached to it).

The Buccleuch Madonna, currently on loan to the National Gallery of Scotland.

In both versions, the infant should definitely figure in anyone’s Ugly Bambino list, but the point of the picture is the cruciform yarnwinder at which he gazes. (A third version in the National Gallery of Scotland (one of up to 40 by followers (this one quite a long way behind) of Leonardo) confirms the association by having the Virgin’s work-basket, with wool on a spindle, at her side. It also has a rather charming background scene of St Joseph with helpers making a wooden baby walker – perhaps St John the Baptist is about to try it out.)

The Madonna of the Yardwinder, NOT by Leonardo da Vinci. (Credit: National Galleries of Scotland)

This kind of yarnwinder is called a niddy-noddy (‘Madonna of the Niddy-Noddy’ doesn’t exactly have the same ring, does it?), and is used at an earlier stage in the thread > textile process, for creating the skeins of yarn which then get transformed into balls using the swift. The crucial thing about the niddy-noddy, clearly visible in all three paintings, is that the crossbars should be at right angles to each other, as in this modern version.

A modern niddy-noddy.

I’m inclined, for lack of evidence, to assume that my little squirrel, busily winding the wool off his swift, is the opposite or antidote to the licentious rabbits on the other side – perhaps it was intended that this side of the flask was the one visible as you carried it along or pulled it out of your pocket, and that the other was for private delectation, perhaps at the address on the spine? But I’d be fascinated to find out more!

Caroline

This was fascinating! Now I know why a friend keeps a water-pistol at the ready to get squirrels off the bird-feeders! I love those Fittzwilliam curiosities!

LikeLike

Thanks, Jackie – I have six bird-feeders in the garden, only one of which is squirrel-proof!

LikeLike

Pingback: Aqila and Prisila | Professor Hedgehog's Journal