‘In regard to plants, no one has treated this subject [natural selection] with more spirit and ability than W. Herbert, Dean of Manchester, evidently the result of his great horticultural knowledge.’

‘In regard to plants, no one has treated this subject [natural selection] with more spirit and ability than W. Herbert, Dean of Manchester, evidently the result of his great horticultural knowledge.’

Charles Darwin, in On the Origin of Species

I blinked slightly, when looking up the noble antecedents of the Hon. and Very Rev. William Herbert (1778–1847), at the statement (in Venn) that he had an uncle called Caroline. Caroline Robert Herbert was born 1751. From Eton, he went to the University of Glasgow in 1770, and became an ensign in the 32nd Regiment of Foot in 1773 (up till that point he had been merely a ‘gentleman’), and ‘retired’ in 1775. He was admitted Fellow-Commoner of Clare College in 1780, and must have been ordained at some point, because, again according to Venn, he was Chaplain to the 1st Dragoon Guards between 1780 and 1782, while simultaneously holding the rectory of Saxmundham, Suffolk, 1780–3.

Caroline Robert moved on to be a chaplain at Portsmouth, 1783–97, and then rector of East Woodhay with Ashmansworth, Hampshire, until his death in 1814. He had acquired a Cambridge LLB in 1787, and left some plate to Clare College. Oh, and his godmother was Queen Caroline, though I am guessing (but who knows?) that his friends called him ‘Bob’ rather than ‘Carrie’.

What Caroline Robert was not, however, was a botanist, unlike his nephew William. Caroline Robert was the younger brother of Henry Herbert (1741–1811), first earl of Carnarvon (the title being a nod, presumably, to the Welsh origins of the Herbert family – he was a grandson of the eighth earl of Pembroke), who had the good fortune to inherit Highclere Castle, where William was born, from an uncle. (It is probably not a coincidence that, although barely being in Hampshire at all (West Roundhay is in Berkshire), East Roundhay is the next parish to Highclere.)

This is the only portrait I have been able to find online of William Herbert. Allegedly painted in 1795 by Sir William Beechey, it appears on a Harvard University website, but with no provenance.

William Herbert was the third son (fifth child) of the earl, and therefore not likely to inherit anything except wealth. After Eton, he went to Christ Church Oxford, matriculating in 1795, but graduating BA from Exeter on 1798; he then moved on to Merton for his MA (he later racked up BCL in 1808, DCL in 1808, and BD in 1840). He resembled his uncle in that the church was not his first career choice: he became an MP for Hampshire (1806–7, ‘after a very expensive campaign’, as the ONDB almost cynically remarks), and later (1811–12) for Cricklade in Wiltshire. However, in 1814, he was ordained, and given the valuable rectory of Spofforth in the West Riding of Yorkshire by another uncle, the earl of Egremont, later being preferred to the deanery of Manchester.

So far, so relatively predictable – including his output of Greek and Latin poetry, and translations from Icelandic and other poems (he even gets a barbed name-check from Byron). Less obvious is his interest in natural history.

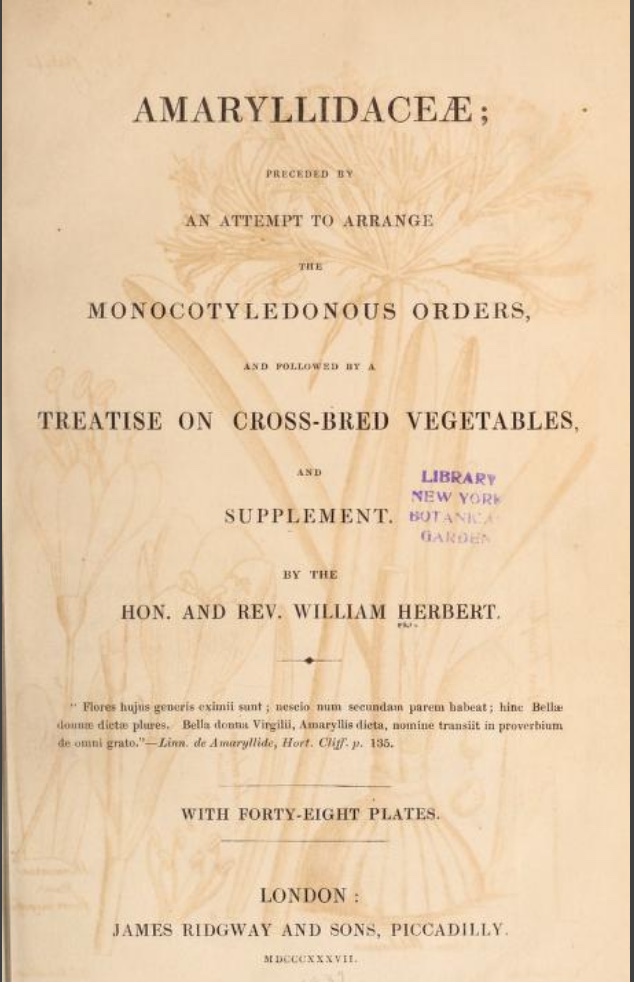

The frontispiece and title page (below) of William Herbert’s 1837 work. (Credit: The Biodiversity Heritage Library)

He was a good shot (lots of specimens acquired that way …) but he also helped to edit the 1833 and 1837 editions of Gilbert White’s Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne, in the County of Southampton. But his big thing was bulbs, and specifically the Amaryllidaceae, on which he published a short but very detailed treatise appended to vol. 7 of the Botanical Register in 1821 and an important and still useful monograph (with 48 plates drawn by himself) in 1837, two of the most interesting aspects of which are his remarks on his methods of raising the plants, and his note of the freedom with which they cross-fertilise. (His importance to this field of horticulture is also noted at some length in Hortus Veitchii.)

The stunning Amaryllis radiata (now Lycoris radiata) from China, a plate from the same volume of the Botanical Register in which Herbert’s 1821 treatise appeared.

He also produced a History of the Species of Crocus, edited after his death by the great John Lindley and published in 1847.

The explanation of the editorial process after Herbert’s death in the Crocus book.

At this point, I modestly introduce one of ‘my’ hippeastrums – mine because I have succeeded in making it flower for a third year running. (Note that I have achieved this only with the most boring (for a Hippeastrum, that is) colour of all, however.)

A red hippeastrum (name long lost), flowering for the third year running.

In the ‘Preliminary Treatises’ to both his works on the Amaryllis family, Herbert attempts the herculean task – given the then (and continuing) confusion between Amaryllis, Hippeastrum, Nerine, Belladona, etc. – of sorting all these bulbous plants out. One feels a slight sigh along with the enthusiasm when he notes at the outset of his ‘Advertisement’ to Amaryllidaceae (dedicated to King Leopold of the Belgians, by the way – and Coburgia is one of Herbert’s suggested (but no longer accepted) names for some species of the genus): ‘The receipt of a fresh supply of valuable specimens, for which I am indebted to Sir W. Hooker, after the printing of the body of this work had been completed, had enabled me to add among the supplemental observations the description of several fine plants before unknown.’

Linnaeus himself had named (in 1759) the type specimen of the species Amaryllis reginae, and it was under this name that Redouté depicted it in his Les liliacées (published by the author in the years 13–24 of the revolutionary but short-lived New Order).

Redouté’s illustration of Amaryllis / Hippeastrum reginae (1802–16).

Herbert changed it to Hippeastrum reginae in his 1821 work, and detailed ten ways, including the shape of the seed, in which he believed the Hippeastrum and the Amaryllis were distinct.

Herbert’s explanation of his choice of the name Hippeastrum.

He chose the name ‘Hippeastrum’ as meaning ‘knight’s-star’ (a Latinising of Greek ἱππεύς and ἄστρον) because of its connection to the term ‘equestris’, which he was already using (there was at one point Hippeastrum equestre, but it is now Hippeastrum puniceum, after renaming by Lamarck).

Hippeastrum puniceum (Lam.), from Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, 1795.

I have seen it suggested that ‘knight’s star’ refers to the shape, supposedly resembling the Morgenstern or ‘morning star’, a flail-like mace which was a medieval knight’s weapon. I don’t find this convincing, and wonder whether it might be a graceful compliment to Thomas Andrew Knight (1759–1838), botanist and horticulturalist of Downton Castle in Herefordshire (no, not Downton Abbey, that’s Highclere), who William Herbert must have known?

Despite (or because of) Herbert’s enormous efforts in distinguishing and refining the differences, Amaryllis/Hippeastrum is still one of the many nomenclature issues among us amateurs, along with Croscosmia/Montbretia, and of course Geranium/Pelargonium. I believe that the rule of thumb is that the Amaryllis comes from South Africa (and there is only one species of it, Amaryllis belladonna), but the Hippeastrum is from South and Central America, where there are over 90 species (Herbert noted 13 in 1821): the cultivars number 600 and rising. And it is these Hippeastrums that are sold before Christmas as ‘Amaryllis’, coming as planted or unplanted bulbs.

The stunning upside-down, walk-underneath display of Hippeastrum hybrids by the Dutch firm W.S. Warmenhoven at the Chelsea Flower Show in 2013.

A friend and I used to size up the prospects in our local garden centre (which starts to stockpile bulbs in October) waiting until they started sprouting (sometimes literally out of their boxes) and were ready to be sold off at reduced price. I do this less often these days, but I’m still a moronic sucker for an alleged bargain: I sent off for a set of four different bulbs at a silly price just before Christmas, and realised of course upon delivery that the price was silly because the size of the bulbs is too. Still, they are at least sprouting, so we will see (perhaps in a year or so, if I am lucky).

The eye of faith can see a millimetre of leaf sprouting in the right-hand bulb. (The pots are 10 cm.)

The RHS advice for keeping the bulbs to flower again is here. I have tried both methods, with varying success, over the years.

My second success of this year, which I suspect will also be red …

My biggest (repeated) mistake is to put them out in the garden in the summer, because wherever I place them they are attacked by slugs who will almost literally jump through hoops and swim across lakes to get at them, not only slashing down the foliage, but chomping off layers of the bulb. But hope none the less springs eternal …

Caroline

Those colour plates are stunning! I must read the advice about keeping Amaryllis over the summer to flower again … I have 3 slug ravaged bulbs in the greenhouse and no new ones this winter. Having to enjoy the stunning plant my mum was given for Christmas, it has 4 beautiful coral and white flowers.

LikeLike

Yes, the bulb companies must really feed them up. My second overwintered one has only two flowers again, but it’s turning out to be a coral colour rather than normal red. But the exposed part of the bulb still shows the deep indentations of slug damage!

LikeLike

Pingback: Hans Hoffmann | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Plant of the Month: January 2020 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: W.P. Milner | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Amaryllis or Hippeastrum Trio? – Go Retire Psychiatrist