A stone’s throw away from the back of Stepney’s enormous churchyard, where the parakeets and pigeons own the sky, and even closer to Lady Mico’s almshouses, is a much smaller cemetery, its gravestones broken, eroded or obscured by the black, sooty pollution of old London. This is the burial ground of the Stepney Meeting, on a small corner plot which once housed almshouses and a school as well.

A stone’s throw away from the back of Stepney’s enormous churchyard, where the parakeets and pigeons own the sky, and even closer to Lady Mico’s almshouses, is a much smaller cemetery, its gravestones broken, eroded or obscured by the black, sooty pollution of old London. This is the burial ground of the Stepney Meeting, on a small corner plot which once housed almshouses and a school as well.

Illegible gravestones …

The 1880 date on this fragment is odd, if the site was closed to new burials in 1853 (see below); but perhaps additions to family tombs and vaults were permitted?

The Stepney Meeting was founded in 1644 by a group of Independents: Henry Barton and his wife, William Parker, John Odinsell, William Greenhill (1591–1671), and John Pococke. (Henry Burton (1578–1648), the vicar of St Matthew’s, Friday Street, whose ears were cropped, along with those of William Prynne, in 1637, for publishing anti-Laudian tracts, was also present.) It was the first Independent congregation in east London.

Henry Burton (with ears intact), by Gustavus Ellinthorpe Sintzenich (1821–92) – the image is presumably taken from a slightly more contemporary print. (Credit: Mansfield College, Oxford)

Greenhill became pastor of the Meeting, and in 1649 (after the execution of Charles I) was appointed by Cromwell as tutor to the royal children briefly in his power – James, duke of York and Henry, duke of Gloucester. He was also made vicar of St Dunstan’s, but unsurprisingly was ejected at the Restoration.

The congregation’s Meeting House was built off Stepney Way in 1674, and rebuilt in 1863. It was reduced to ruins by bombing in the Second World War, and the site was incorporated into the wonderful Stepney City Farm, though at present the area is a bit of a wreck as massive engineering works are going on to provide not (as I naively believed) a station for Crossrail, but just an enormous air vent. (I understand that, once the works are completed, the land will go back to the farm.)

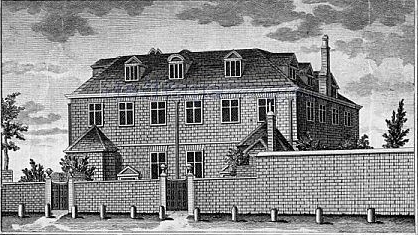

The Stepney Meeting House in 1783.

Fragments of the bomb-destroyed nineteenth-century Meeting House.

Greenhill’s successor at the Meeting was Matthew Mead (1628?–99) from Leighton Buzzard in Bedfordshire, a scholar of Eton and King’s College, Cambridge, where he became a fellow in 1649.

Matthew Mead, also by Sintzenich – the same caveat about authenticity applies. (Credit: Mansfield College, Oxford)

His life, on the Puritan end of the Anglican spectrum, was dominated by the politics of the Civil War and its aftermath, and included a post as ‘morning lecturer’ at St Dunstan’s, Stepney (thanks to Greenhill), but he was ejected from all his positions at the Restoration, and though he continued to preach (he apparently had a private income, and was wealthy in both cash and property upon his death), he was suspected of sedition and had many run-ins with the government throughout his life.

Mead was called as pastor of the Independent church at Stepney after Greenhill’s death, on 13 October 1671, and ordained on 14 December, and it was during his period of service that the Meeting House was built. However, he was later implicated in the Rye House Plot (for which he was imprisoned) and Monmouth’s Rebellion (after which he fled to the Netherlands). Unsurprisingly, he stayed abroad (in Amsterdam and Utrecht) after the succession of James II, but was pardoned and returned to England in 1687, after publicly praying most earnestly for the king, to the consternation, apparently, of his fellow exiles.

Matthew Mead in 1683, by the engraver Robert White (1645–1703). (Credit: the National Portrait Gallery)

However, by 1689 he was giving public thanks for William III’s victory, and at this point he returned to Stepney, being given a house to live in next to the Meeting House. He spent the remaining ten years of his life often still in controversy, but also in attempting to reconcile the various non-conformist sects, while raising money for needy clergymen. He was buried near the south door of St Dunstan’s church.

This map of 1870 has been annotated to show the position of Mead’s tomb, but I’m not sure I have located it (it may be that it’s not as described).

The burial ground was, apparently, originally used for the deceased inhabitants of the Mico almshouses, and was known as the Mercers’ Burial Ground. The Meeting took it over in 1779, and built its own almshouses, (for eight old women), and in 1785 a schoolhouse, which was in use until 1821.(Sadly, I couldn’t find out anything about this building, but it must have been tiny.)

The burial ground on the 1870 map.

The end of the row of almshouses in the late nineteenth century.

The view from the almshouses across the burial ground in the late nineteenth century.

Burials ceased in 1853, and over a hundred years later, in 1976, the space was opened as a park. Very few of the original tombstones remain, but there are apparently fourteen large crypts underneath – I assume that the large concrete slaps with iron strips on them are modern covers for two of these.

The view across the burial ground, with one of the crypt covers (??) in the foreground.

A surviving family tomb.

Somewhat disconcertingly, the triangle of short terraces whose communal garden backs on to the burial ground are on a lower ground level, and also have basements.

Looking down from the burial ground to the ground level of the surrounding houses.

One of the buttresses of the burial ground retaining wall, from the other side.

One hopes that the heavy buttressed walls are keeping in place the contents of the graves and vaults, and that the local groundwater is not affected …

Caroline

Pingback: The 205 | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: St Jerome | Professor Hedgehog's Journal