Winding back a bit from our recent trip to the Netherlands, we had the great good fortune to spend ten days in Italy at the end of April, of which three were in Ravenna before going up to Venice by train. This was before the disastrous floods in the area in the middle of May, when several people died and thousands were made homeless, and I am getting increasingly frustrated by the lack of information online about any damage suffered by the wonderful monuments in this UNESCO World Heritage area, where the potential for massive flood damage was outlined in an article back in 2018.

In this context, and especially having seen photos of the Museum at Sant’ Apollinare in Classe (up a little hill) being used as a refugee centre with camp beds between the exhibits, the following may seem a bit frivolous, but anyway … Having visited the two churches dedicated to Sant’ Apollinare, in Classe and in Ravenna itself, it occurred to me that I didn’t actually have the faintest idea who this saint was, except that he clearly loved sheep. And did he have any connection with Apollinaris water?

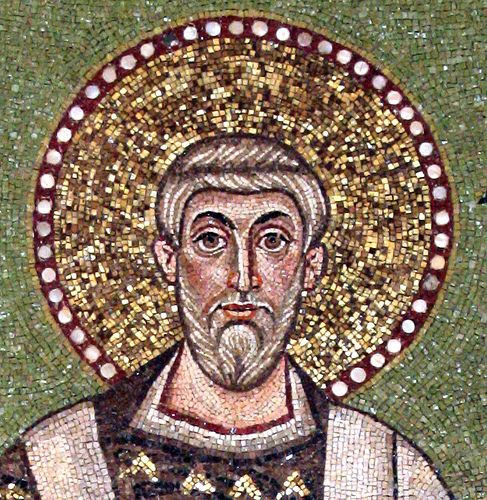

The saint is supposed to have come from Antioch (now Antakya in Turkey) as a disciple of St Peter himself, and was ordained by him as the first bishop of Ravenna, during the reign of the Emperor Claudius, so between 41 and 54 CE.

Other accounts suggest that he lived in the second century CE, and was martyred in the reign of Septimius Severus. Either way, the city apparently had a small Christian community, but Apollinare was in constant danger from the ‘pagan’ Romans, especially as his miraculous cures of the sick (and at least one resurrection from the dead) caused large numbers of conversions to Christianity.

He was frequently beaten by the Roman authorities, and on one occasion forced to walk on hot coals, which however failed to burn him. After being imprisoned and loaded with chains, he was put on a ship and sent into exile, but the ship was wrecked, and Apollinare came to shore in Mysia (modern Turkey). There, the oracle of the god Serapis refused to speak until the Christian was driven out (shades of Milton’s ‘On the Morning of Christ’s Nativity’: ‘The Oracles are dumb; / No voice or hideous hum / Runs through the archéd roof in words deceiving’), and when he was discovered (having been sheltered by local Christians) he was put on another ship, back to Ravenna.

There he was again denounced, and put under the guard of a centurion who was in fact a secret Christian and allowed him to escape. Recaptured, he was beaten so severely that seven days later he died, probably at Classe, and his body was buried near the city walls.

So far, so normal among the accounts of early saints and martyrs: even the confusion of up to a century or more about his dates is not unusual; and his day is also confusing – it used to be 23 July, the supposed day of his death, but that date was later assigned to St Bridget of Sweden, and relatively recently he was given 20 July, an apparently vacant date in the Catholic calendar (though what about St Wilgefortis or Uncumber, I hear you ask?).

He is invoked against gout, epilepsy, and diseases of the sexual organs, and the connection with Apollinaris water (discovered in a spring in Bad Neuenahr, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany in 1852) is because he is also a patron of wine – though I can’t find more than a single source claiming this. There is, however, a church of St Apollinaris in Napa Valley, California.

But just to show how everything is connected to everything else, in 1872 the medical journalist Ernest Hart dined with George Smith (1824–1901) of the publishing company Smith, Elder and Co. (Jane Eyre, works of John Ruskin, Cornhill Magazine, Darwin, Thackeray, the Brownings, etc. etc.), and recommended the water to him. Smith mentioned it to a business colleague, Edward Steinkopff, who then started to import it to Britain, from an office off Oxford Street. It took off, and Wikipedia has an enchanting list of ‘cultural references’ to it, from Trollope to Henry James and Dorothy L. Sayers.

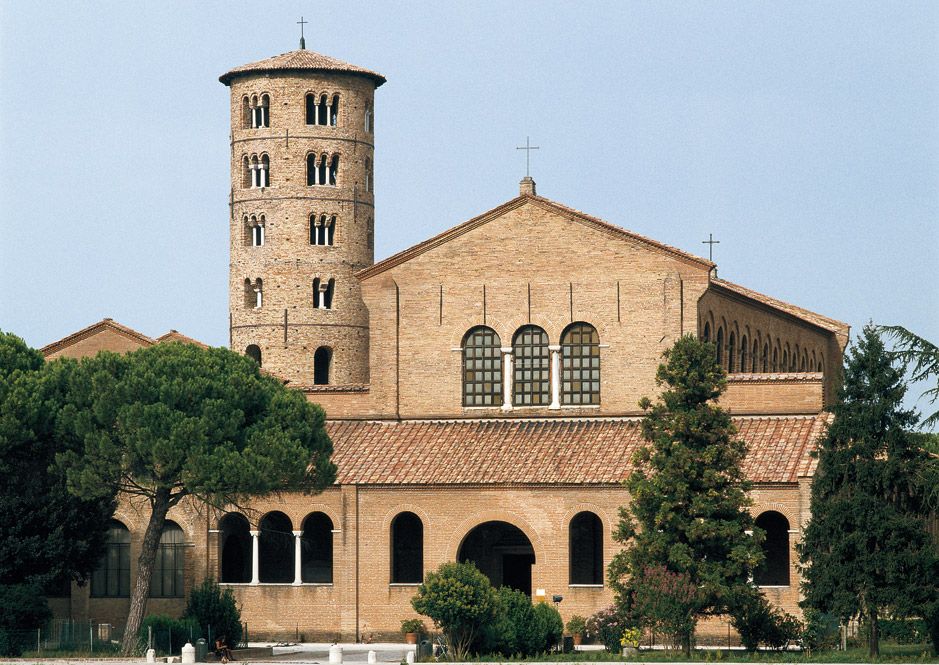

Getting back to the saint, what seems to me to be unusual about a minor, if not mythical, figure is the spread of his cult across Europe, and the glorious art and architecture of the churches dedicated to him. The church of Sant’ Apollinare in Classe was begun early in the sixth century, during the reign of Theodoric the Ostrogoth, on the orders of Bishop Ursicinus, using money given by one Julius Argentarius, a banker who also funded the building of San Vitale in Ravenna, and was consecrated on 9 May 549 (by which time Ravenna was back in ‘Roman’ hands, under Justinian) by Bishop Maximian.

The building itself is relatively plain, though majestic, on the outside:

but of course its glory is the interior, from the apse in which the saint stands in a flowery meadow surrounded by sheep, his hands raised in blessing, to the walls in which angels, saints and martyrs are depicted. The relics of the saint were translated there, but they were moved again when Classe diminished as a port, with the silting up of the estuary, and raids by pirates became increasingly frequent.

The ‘new’ Sant’ Apollinare in Ravenna itself was originally built as the palace chapel of Theodoric, and dedicated to Christ the Redeemer in 504 CE. Under Justinian it was reconsecrated to St Martin (and any Arian tendencies in the decoration removed), but when the relics of the saint were brought from Classe in 856, the church was rededicated to him.

Elsewhere in Italy, the church of Sant’ Apollinare in Rome was founded by Pope Hadrian I in about 780, and rebuilt in 1742 by the orders of Pope Benedict XIV. In more recent years, sadly, it has been tainted by the mystery of the disappearance of Emanuela Orlandi in 1983, a horrible mess of conspiracy theories about the connection of the Vatican with sexual impropriety and organised crime. (There used to be a church dedicated to the saint in Bologna, but it was demolished in 1250.)

Meanwhile, in France, King Clovis built a church near Dijon, according to several sources, but I can’t find any details about it. However, between 1118 and 1120 Duke Bořivoj II of Bohemia founded one in Sadská, in the Czech Republic, and there is also a church in Prague, established about 1360 by Charles IV.

Perhaps the most famous church outside Italy dedicated to the saint is at Remagen (also in the Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany): an extraordinary-looking pilgrimage church, originally a chapel of St Martin (the hill was formerly called the Martinsberg), founded in the remains of a Roman fort. It is claimed that a boat sailing from Milan to Cologne bearing religious relics (did it include those of the Magi?) was stopped dead in the river in 1164 and was not able to move on, in spite of the strong current, until some bits of Sant’ Apollinare were put ashore and interred in the chapel, after which the boat was able to proceed. (Against this version is another possibility, that the relics (whatever they are), which now lie in the crypt, arrived at the end of the fourteen century, the first pilgrimage being recorded in 1384.) The present church was built between 1837 and 1852, a spectacular example of neo-Gothic, with interior frescos painted by members of the Nazarene movement which include scenes from the life of St Apollinaris.

As well as Ravenna and Remagen, Saint Lambert’s Church in Düsseldorf is alleged to hold some of his relics, and he is the patron saint of that city. (Did the boat containing the relics have another enforced stop here on its way down the Rhine?)

As far as I have been able to discover, there was/is only one other St Apollinaris (as opposed, for example, to the many St Clements): St Claudius Apollinaris the Apologist, bishop of Hierapolis in Turkey. In spite of the many uncertainties surrounding his life, we must be grateful that Ravenna’s Sant’ Apollinare was the inspiration for so much wonderful art. And let us hope that his sheep continue to graze safely and above the water line.

Caroline

A wonderfully detailed account not only of St Apollinaire’s life but of the many beautiful churches dedicated to him. Thank you for giving us these pictures and accounts .

LikeLike

Thank you, Clare!

LikeLike