It is far too long since I last managed to complete a blog. I continue to be permanently exhausted, and my brain is mush – so much so that when I wanted to add an updating link to my 2020 piece on Maarten van Heemskerck, I managed to delete the entire thing, and it took two days to reconstruct it. I have begun several pieces which remain unfinished through a lack of energy and the said mushy brain …

However, I had the good fortune (and privilege) to attend a dinner at the Mansion House in London recently (this is in the context of Him Indoors’s charitable activities, rather than because of any innate virtue of my own), and was stunned for the second time (having been previously, about a year ago) by the incredible collection of Dutch and Flemish paintings on the walls.

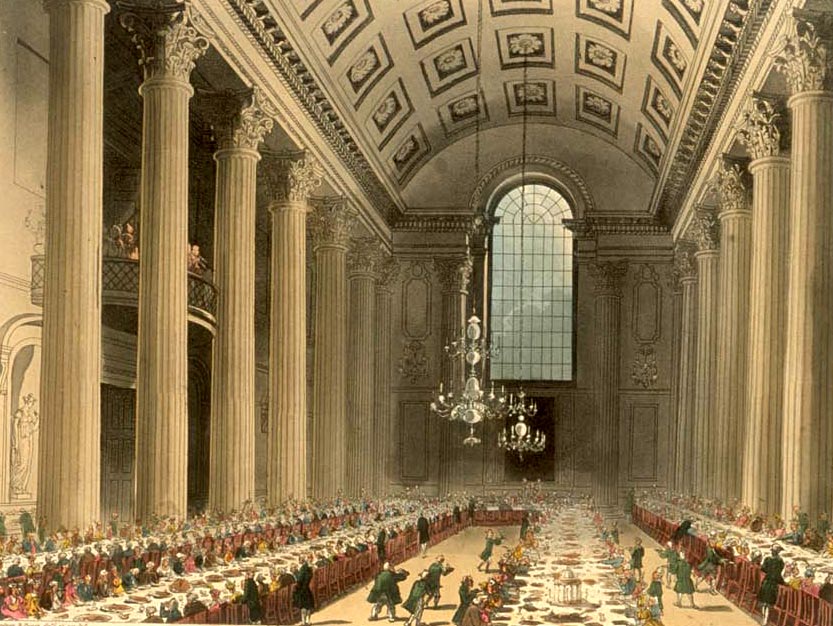

Hung in various rooms in the building originally designed by Charles Dance the Elder (1695–1768) and completed in the Palladian style in 1752, the paintings show the range and depth of Dutch Golden Age art, from portraits to still lives and landscapes, and I doubt if I have yet seen them all properly, as walking from one to another with a pre-meal glass of something fizzy in one’s hand, though delightful, is not a serious way to look at art.

When I was wandering around last year, several of the pictures looked familiar to me, but it was only when I found Nicolaes Maes’ A Young Woman Sewing that the penny finally dropped.

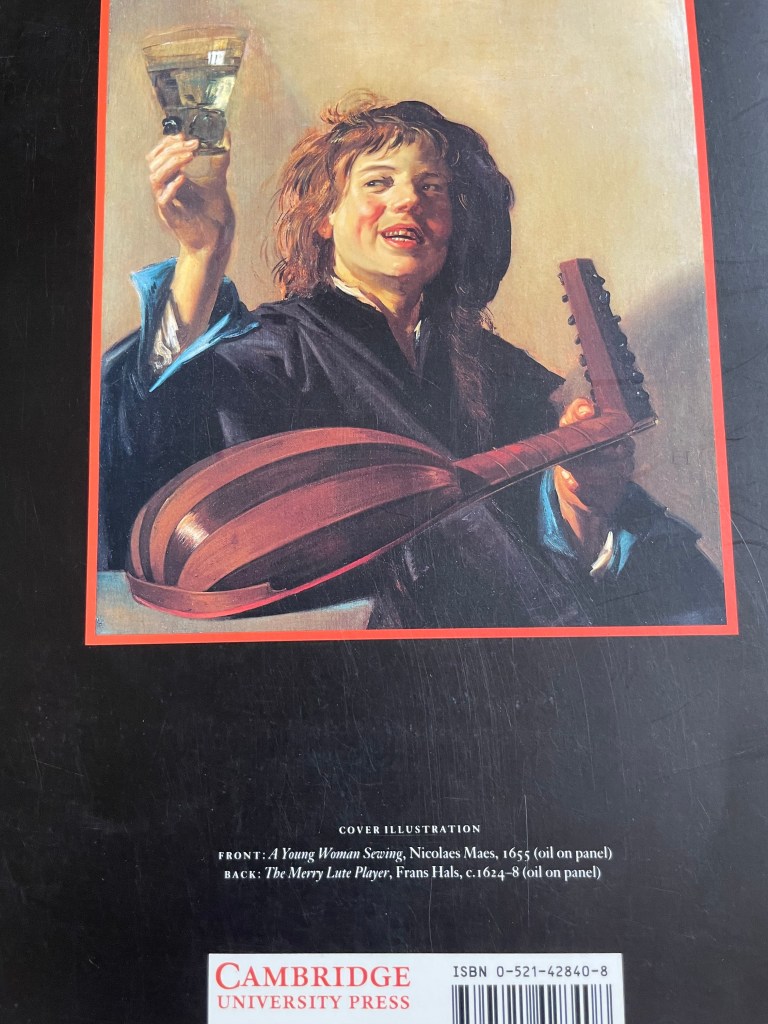

It is the cover picture of a book by Peter C. Sutton for the production of which I was responsible in a previous life (in 1992 to be precise, though when I got hold of a copy it was a 1997 reprint).

On the back cover is a famous Hals picture, which is the first one you see when you begin to ascend the stairs to the reception rooms above. And throughout this spectacular area there are dozens more portraits, landscapes and still lives from the Dutch Golden Age.

They were the bequest of Sir Harold Samuel (1912–87), Baron Samuel of Wych Cross, a businessman and generous philanthropist, who bequeathed his art collection to the Corporation of London. Samuel was a very successful property developer, who after living in Hampstead moved to Wych Cross Place in Sussex.

As Sutton points out in the catalogue (p. 2), the majority of the paintings are quite small, and mostly painted on oak board or copper rather than canvas. Lord Samuel relied almost exclusively on one dealer, Edward Speelman (1910–94), for most of his acquisitions. Speelman’s father was an art dealer, originally from the Netherlands, and during the Second World War, the son, serving as an intelligence officer, was appointed as a liaison officer between the Dutch and British forces, and personally arrested Artur Seyss-Inquart, the Reich Commissioner for the Netherlands, who was subsequently hanged as a war criminal.

Alphabetically, the artists in the collection range from Arent Arentsz., also known as ‘Cabel’, to Philips Wouwermans, and the number of the paintings is 84 (now 83: see below). The only significant artist missing is Rembrandt, but everyone from Avercamp to de Hooch to the van Ruysdaels (and many others) is represented.

(Credit: City of London Corporation; http://www.artuk.org)

(Credit: City of London Corporation; http://www.artuk.org)

(Credit: City of London Corporation; http://www.artuk.org/)

(Credit: City of London Corporation; http://www.artuk.org/)

(Credit: City of London Corporation; http://www.artuk.org/)

In his dealings, Speelman almost inevitably handled some art which later turned out to be Nazi-looted, and one of the paintings he sold to Lord Samuel, The Oyster Meal, by Jacob Ochterveldt, was later discovered to have been the property of Joan Hendrik Smidt van Gelder (1887–1969), a Dutch paediatrician who worked in Arnhem and whose property, along with the rest of the town, was looted by the Nazis in January 1945.

It vanished until 1965, when it appeared in an auction in Zurich without a provenance and was bought by an American diplomat, John William Middendorf II. In 1971 it was in Speelman’s possession, and purchased from him by Lord Samuel. In 2017 it was identified as looted art, and the Corporation of London returned it to van Gelder’s daughter, who was then 96. In 2018 it was sold at auction and the proceeds divided among van Gelder’s descendants.

There is obviously much more to be found out about this collection and the Mansion House in general. Tours are available, so I need to pull myself together sufficiently to go on one. And I very much hope that there will not be as big a gap between this blog and the next one as there was between cork oak in January and the Mansion House in August!

Caroline

Glad to see you back!

LikeLiked by 1 person

So glad to hear from you again. You always feed us the best mind- and heart-nourishing fare. Thank you. Sandra Hyslop in Portland Oregon USA

LikeLike

Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Thank you, Jennifer, you are very kind!

LikeLike

Terrific to see you back: I really enjoy your posts.

LikeLike

Always great to read your blogs, and I always learn so much

LikeLike

Thank you so much for these kind words!

LikeLike

My hope is to form a habit – in so far as I can – to visit your blog. Came across it by way of Twitter. It reminds me of stuff in Cabinet magazine.

LikeLike

Thank you! I am trying to work on two at the moment, but the brain mush remains, alas!

LikeLike