Last night, I went on one of the wonderful Allan Brigham’s Cambridge ‘Town not Gown’ walks, intended by Allan (a Cambridge Blue Badge Guide) to introduce the inhabitants of Cambridge to some of the less familiar aspects of their city. It is his intention that everyone should finish the walk knowing something they didn’t know before: this was achieved spectacularly for me at St Andrew’s Church, Chesterton.

Last night, I went on one of the wonderful Allan Brigham’s Cambridge ‘Town not Gown’ walks, intended by Allan (a Cambridge Blue Badge Guide) to introduce the inhabitants of Cambridge to some of the less familiar aspects of their city. It is his intention that everyone should finish the walk knowing something they didn’t know before: this was achieved spectacularly for me at St Andrew’s Church, Chesterton.

One of the series the Cambridge Library Collection publishes is ‘Slavery and Abolition’, within which I had come across, and written about, the biographies of three African ex-slaves who had ended up, after various appalling experiences, in Britain. I knew that one of them, Olaudah Equiano (whose slave name was Gustavus Vassa), had married a Cambridgeshire girl (who I mistakenly said was from Soham: they married at St Andrew’s church, Soham, but she was from Fordham).

I wondered vaguely at the time how the London-based (though widely travelled, in the cause of anti-slavery) Equiano had met Susannah Cullen, from this tiny Cambridgeshire village. It has been suggested that she was a subscriber to his autobiography, but her name does not appear in the subscribers’ list in the first edition of 1789 (where among the ‘C’s are ‘The Rev. Mr. Thomas Clarkson, 2 copies’, ‘Richard Cosway, Esq.’ (the famous miniaturist, who had sheltered Cugoano), and ‘Ottobah Cugoano, or John Stewart’ himself, another British ex-slave and active abolitionist).

This Rubens-like etching of himself and his wife by Richard Cosway may depict Cugoano as the servant offering fruit.

However they met, Gustavus (as he continued to call himself) and Susannah were married on 7 April 1792, and made their home in Soham, where their two daughters, Anna Maria (born 16 October 1793) and Joanna (born 11 April 1795) were baptised in the church. Equiano also spent time at various addresses in London, where he died on 31 March 1797 (his burial place is not known). Susannah had died on 21 February 1796, and was buried at Soham, her gravestone bearing the inscription ‘Susannah Vassa, Wife of Gustavus the African, aged 34 years’.

Tragically, the elder of the two orphaned girls, Anna Maria, died a few months after her father, on 21 July 1797, at the age of four. What I had no idea of was that she was buried in the churchyard of St Andrew’s, Chesterton, where I had never noticed the memorial plaque to the left of the church porch (apologies for the bad photo, the best I could do).

The inscription reads:

Near this Place Lies Interred

Anna Maria Vassa

Daughter of Gustavus Vassa, the African

She Died July 21 1797

Aged 4 Years

Should simple village rhymes attract thine eye,

Stranger, as thoughtfully thou passest by,

Know that there lies beside this humble stone

A child of colour haply not thine own.

Her father born of Afric’s sun-burnt race,

Torn from his native field, ah foul disgrace:

Through various toils, at length to Britain came

Espoused, so Heaven ordain’d, an English dame,

And follow’d Christ; their hope two infants dear.

But one, a hapless orphan, slumbers here.

To bury her the village children came.

And dropp’d choice flowers, and lisp’d her early fame;

And some that lov’d her most, as if unblest,

Bedew’d with tears the white wreath on their breast;

But she is gone and dwells in that abode,

Where some of every clime shall joy in God.

A local resident told us that next Sunday (the nearest to the date of Anna Maria’s death) is ‘Vassa Day’, at which the children of the village lay flowers at the memorial.

St Andrew’s church, Chesterton. Anna Maria’s memorial is on the wall to the left of the porch (here hidden by the yew tree).

The infant Joanna survived, the heiress of a legacy of about £950, partly made up from the income from her father’s best-selling book. Not much is known about her early life and upbringing, but on 29 August 1821 she married a Congregationalist minister, Henry Bromley: they subsequently lived in Devon and Clavering in Essex, before moving to London (apparently for Joanna’s health). She died on 10 March 1857, and was buried in Abney Park cemetery, the then new non-denominational burial ground in Hackney. Her damaged grave was rediscovered in 2005, and restored just before the 150th anniversary of her death. It is not known whether she had any children.

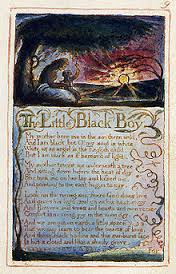

The reason for the young Anna Maria’s burial at Chesterton is not known: were there relatives of her mother in the village? And who wrote the memorial poem (someone who was acquainted with William Blake’s ‘The Little Black Boy’, published in 1794, I suspect)?

A number of unanswered questions, but I certainly came out of yesterday’s walk knowing one remarkable fact of which I had previously been unaware – thanks, Allan!

Caroline

Thank you. Allan

LikeLike

Pingback: Retirement: Four Months In | Professor Hedgehog's Journal