Moving on from the edible apples of autumn, it’s appropriate to consider the golden apples of the Hesperides, which can be viewed at the Fitzwilliam Museum, down the road from the Botanic Gardens in Cambridge, in a small exhibition on Heracles/Hercules in the history of western art (open until 6 December).

Moving on from the edible apples of autumn, it’s appropriate to consider the golden apples of the Hesperides, which can be viewed at the Fitzwilliam Museum, down the road from the Botanic Gardens in Cambridge, in a small exhibition on Heracles/Hercules in the history of western art (open until 6 December).

My object this month is taken from this exhibition: an plate by the famous Dutch engraver Hendrik Goltzius (1558–1617) showing Hercules leaning on his club, taking a rest after completing his eleventh labour, three golden apples in the hand behind his back.

This is the ‘Farnese Hercules’, a statue discovered at the baths of Caracalla in Rome in 1546. It was carved early in the third century CE, but almost certainly based on a Greek bronze of the fourth century BCE, and has itself been much imitated ever since.

In this ‘Capriccio’ of Roman ruins by G.P. Pannini, the Farnese Hercules is put into unreal juxtaposition with the Pantheon, Trajan’s Column, a massive stone urn, and other architectural fragments.

In my nerdy youth, I could recite the labours of Heracles in canonical order, but just now I had to look them up. His instructions, from his crafty cousin Eurystheus, king of Tiryns (aided and abetted by Hera) were:

- Slay the Nemean lion; 2. Slay the Lernaean hydra (snake with nine heads); 3. Catch the Cerynian hind (swiftest animal on earth, sacred to Artemis); 4. Catch the Erymanthian boar; 5. Clean the filthy stables of King Augeas of Elis (in a single day); 6. Slay the Stymphalian birds (swamp-dwelling man-eaters with bronze beaks); 7. Catch the Cretan bull (possibly an in-law of the Minotaur); 8. Steal the mares of Diomedes (man-eating bloodstock owned by the king of Thrace); 9. Get hold of the girdle of Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons; 10. Steal the cattle of Geryon (who according to various sources had one body and three heads, or three bodies, or six hands and feet: a bit of a monster in any event); 11. Steal the golden apples (bestowers of immortality) of the Hesperides, from a garden owned by Hera and guarded by the Nymphs of the Evening plus a hundred-headed, sleepless dragon; 12. Bring the three-headed watchdog of Hades, Cerberus, back from the Underworld.

Ink through the generations from ancient Greece onwards has been spilt in trying to locate the sites of the deeds, interpret them as myths, folk-memory, hero-tales or true(ish) history and generally extract all the possible symbolic and literal meaning from them. Conquest by one tribe of others in the Peloponnese (Nemea, Lerna, Elis)? Exotic tales of a battling hero transmitted from Ionia and further east? (Some of the labours resemble those of the Sumerian hero Gilgamesh.) Early exploration of the western Mediterranean, the Black Sea and Scythia?

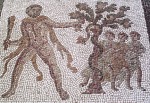

In this Attic black-figure vase in the Louvre, Hercules attacks Geryon, who has three heads, three shields and six legs.

But the final two labours (which, some scholars argue, were not originally part of the canon, being added on to justify Heracles’ status as an immortal demigod) seem to move out of the realm of folk-tale (man-eating horses, three-headed men) into something stranger. Golden apples crop up (ho ho) in many traditions: Russia, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Azerbaijan, Scandinavia (the apples of Freia, goddess of youth, without which all the gods would weaken and die), later transmogrified by Wagner into a Leitmotiv), as well as Greece and Rome.

A red-figure vase showing three of the Hesperides with the magic apple tree, and Ladon the snake twisting round the trunk.

A modern Wedgwood plaque deriving from the image above: Hercules sits next to the nymph on the right of the tree.

Some of these apples – though not presumably the far northern ones – may have been quinces or pomegranates: but golden apples appear several times in Greek myth. Atalanta, the fastest runner in the world, was defeated in a race by her devious suitor Meleager, who threw a pretty golden apple in her path to distract the silly girl and so get past her.

And another golden apple of course started the Trojan War: the fatal fruit engraved with the words ‘For the fairest’ which caused discord among the goddesses and led to Aphrodite’s promise to the Trojan prince Paris that, in return for being awarded the prize, she would give him the most beautiful woman on earth.

In this version of the Judgement of Paris (in the Galleria Cini in Venice), Botticelli has not followed the normal convention of depicting the three goddesses naked.

The golden apples taken by Hercules (some say by the giant Atlas, while Hercules had taken on his burden of holding up the world) could not be kept: Athena took them back to the garden after Eurystheus had agreed that the labour had been accomplished. The same thing happened with the twelfth and final labour: Cerberus the guardian beast of the Underworld, having been either wrestled into submission by Hercules or drugged with a doctored honey-cake, terrified Eurystheus so much that he ran off and hid in a huge jar; but Hades’ pet was then returned to him.

There has always been an ambivalence about Hercules the hero. The son of Zeus, he was implacably hounded by the jealous Hera, who unsuccessfully sent a pair of snakes to kill him in his cradle.

The twelve labours for Eurystheus were undertaken to expiate the crime of murdering (in a fit of goddess-induced madness) his wife and children; and of course the end of his mortal life was horrific – immolating himself on a funeral pyre of uprooted trees after his (second) wife unwittingly dressed him in a poisoned robe. But the fascination of the tales about him, with their almost endless variants and echoes of other ancient cultures, to say nothing of their impact on later Western civilisation, is beautifully represented in this small but perfectly formed exhibition – don’t miss it!

Caroline

Pingback: Object(s) Of The Month: March | Professor Hedgehog's Journal