The botanical theme continues, because I have just acquired a lovely book, The Plant Kingdoms of Charles Jones, by Sean Sexton and Robert Flynn Johnson, on the recommendation of the estimable Gentle Author, on whose blog you can see some of the wonderful photographs it contains, and read the all-too-brief story of what is known about the gardener Charles Jones who took them.

The botanical theme continues, because I have just acquired a lovely book, The Plant Kingdoms of Charles Jones, by Sean Sexton and Robert Flynn Johnson, on the recommendation of the estimable Gentle Author, on whose blog you can see some of the wonderful photographs it contains, and read the all-too-brief story of what is known about the gardener Charles Jones who took them.

My second-hand copy used to belong to Finsbury Library, where it was borrowed once, on 9 April 1999. Finsbury Library’s loss is my gain, though it’s a relief to see online that the library itself still exists: you can never be sure these days, especially in London.

The plates themselves are stunning: as the famous chef Alice Waters says in her foreword, ‘Of course, the photographer would have had to be a gardener, or a cook – and a good one, with a clear, unjaded eye.’ The images glow with a sort of steely light, and although they are monochrome, some, such as the ‘Monarch’ plum, seem to emit colour. Jones apparently used plate-glass negatives which produced gelatin-silver plates, and noted in pencil on the back what variety of fruit, vegetable or flower the photo was.

Sadly, in old age, Jones used the glass plates themselves as cloches: as far as is known, none have survived. (This rings a bell: the same thing happened to the plates of a pioneering woman photographer in Adam Thorpe’s Ulverton.) The photographs were discovered by Sean Sexton in an antiques market in 1981, and a selection was published in the book in 1998.

I thought I’d have a look at two things in the background of this story: the location of Jones’s garden, and the varieties of plant he chose to photograph. One of the few certain references to his life is that, for some years before 1905, he was gardener at Ote Hall in Sussex, where his work – especially his fruit – got a rave review in the Gardener’s Chronicle in September.

Ote Hall (now Great Ote Hall), in the parish of Wivelsfield, near Burgess Hill, East Sussex, is a lovely looking place, dating from the fifteenth century and now used as an event venue. Some of the photographs show sections of an herbaceous border – is this part of the one created by Jones?

A brief history of the estate shows that in 1537 it passed into the hands of the Godman family, who have owned it – with some breaks – until the present day. In 1881 it was acquired by Major-General Richard Temple Godman (1833–1912), a veteran of the Crimea, who had taken part in the charge of the Heavy Brigade at Balaclava – less famous than that of the Light Brigade, because (thankfully) it was successful, rather than a tragic blunder – and it must have been as his gardener that Jones carried out his work.

In 1923, the house was bought by one Ernest J. Enthoven, who died in 1936, at which point his son sold the house (back) to the trustees of the Godman family. The Enthoven name rang two more faint bells. Ernest J. Enthoven produced (in 1903) an edition of the Parentalia, the biography of Christopher Wren by his son (I was formerly involved in an earlier version of the same work). The son, Roderick Eustace Enthoven (1900–85) was one of that extraordinary group of people whom we have recently started to call (after the book by Robert M. Edsel and the rather disappointing film by George Clooney) the Monuments Men.

An architect and illustrator, he began his war service as a camouflage officer, but in August 1944 was sent (with the rank of Captain) to Italy as part of the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives programme, first in Florence, then in Piemonte and the Veneto. Among his achievements was the return of Giambologna’s monumental equestrian statue of Cosimo I de’ Medici to its place in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, of which there is an account here.

With the modesty characteristic of so many returning servicemen and women, in 1946 Enthoven gave a lecture about his experiences to the Architectural Association, which was published in their journal. He then went back to civilian life, and was briefly librarian at RIBA before resuming his own architectural practice.

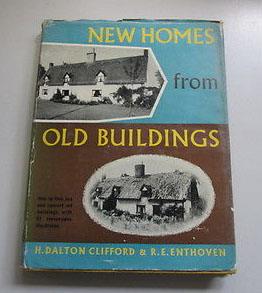

One of his publications was New Homes from Old Buildings (co-written in 1954 with H. Dalton Clifford): ‘How to find, buy and convert old buildings, with 31 conversions illustrated’.

One wonders if his early experience of living at Ote Hall, and his period among the ruins of Italy, had influenced his conservationist views, at a time when so many architects were planning to build a forward-looking, ‘futuristic’ world (which would contain e.g. the new Finsbury Library) out of the rubble of the old?

I’ve almost run out of space without even getting on to the heritage plant varieties: they will have to sit glowing on their pages for another occasion …

Caroline

Pingback: Ghostly Vegetables (Part 2) | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: Ghostly Vegetables (Part 3) | Professor Hedgehog's Journal