Though the constant thread running through his adult life was radical journalism (for which he spent most of the years 1810–12 in Newgate prison), William Cobbett (1763–1835) had many careers: farmer, soldier, grammarian, language teacher, author, economist, printer, publisher, Member of Parliament – and nurseryman. A plant and seed catalogue published by him (from internal evidence, one of a very frequent series, this issue dating to 4 December in a year after 1826) has just come to light in the archive which I am helping to sort through, and it is completely characteristic of the man.

Though the constant thread running through his adult life was radical journalism (for which he spent most of the years 1810–12 in Newgate prison), William Cobbett (1763–1835) had many careers: farmer, soldier, grammarian, language teacher, author, economist, printer, publisher, Member of Parliament – and nurseryman. A plant and seed catalogue published by him (from internal evidence, one of a very frequent series, this issue dating to 4 December in a year after 1826) has just come to light in the archive which I am helping to sort through, and it is completely characteristic of the man.

‘Normal’ nurserymen produced lists of their various wares, with prices and the occasional short description. Cobbett issues a sixteen-page tract entitled ‘Catalogue of American Trees, Shrubs, Plants, and Seeds, For Sale by Mr Cobbett’. Priced at twopence, and ‘Printed by W. Cobbett, No. 183, Fleet-street, London’, it begins bullishly:

The opening of Cobbett’s address to his potential customers.

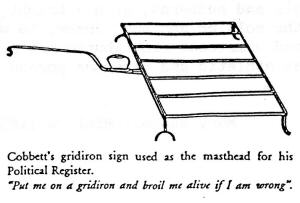

The ‘Office of the Register’ (at 183 Fleet Street) was then the centre of Cobbett’s journalistic activities. His Political Register was published almost every week between January 1802 and his death, and was the first newspaper to set out its political stance (Cobbett’s own) in regular leading articles.

The ‘logo’ of the Political Register.

He was born in Farnham, Surrey, where his father was a farmer and ran a pub: William famously described himself as ‘bred at the plough-tail’. His formal schooling seems to have been minimal: he was taught by his father, and then became a voracious autodidact after joining the army.

Cobbett leaves the plough (and gibbet) and joins the army: an 1809 cartoon by James Gillray.

His literacy caused Cobbett to be promoted to sergeant-major and clerk to the regiment, but his inside knowledge of the administration convinced him that corruption was rampant, and on his discharge in 1791 he attempted to have some of his officers court-martialled. Predictably, this put him in danger, and in February 1792 he and his new wife Nancy fled, first to France for six months and then to America until 1800, when a threat of a libel case caused their return (now with two children) to England.

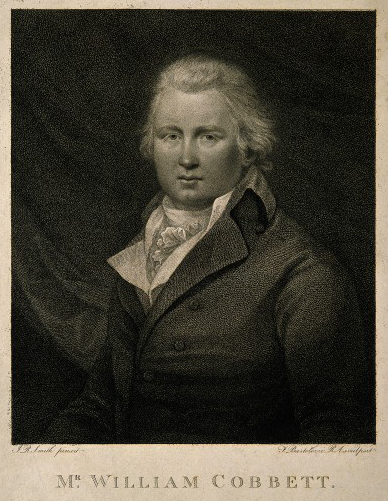

William Cobbett, from a stipple engraving by F. Bartolozzi, 1801. (Credit: Wellcome Library, London)

Returning in some sense to his roots, Cobbett’s focus in the Political Register gradually moved from metropolitan politics to rural affairs, and in 1805 he bought a farm in Botley, Hampshire, where he entertained the county gentry (including on one occasion the Mitford family, as recalled by Mary Russell Mitford in the 1883 edition of her Recollections of a Literary Life).

But his continued zeal for radical politics, and particularly parliamentary reform, caused him to flee to the United States again in 1817, leasing a farm in Long Island, and publishing in 1818 his cheeky Grammar of the English Language, intended to benefit ‘soldiers, sailors, apprentices, and plough-boys’, and taking its examples of bad grammar from the utterances of the highest in the land; and also his Year’s Residence in the United States of America, which describes the climate, soil and crops he observed and the vegetables he grew, as well as the economics of farming in America, American customs, laws, and religion.

On his return to England in 1819, Cobbett was bankrupt, and lost the Botley farm. Undaunted, and doubtless bolstered by the bones of the great radical Thomas Paine which he brought back with him, he espoused the cause of Queen Caroline before and during her trial, and sales of the Political Register soared, so that he was able to begin a nursery to raise imported American plants over four acres in Kensington, then a healthy rural spot outside London; nearby Kensington Gravel Pits (now Notting Hill Gate) was shortly to become a popular address for artistic and literary types.

The Kensington turnpike in 1820.

The catalogue begins with a description of the way he runs his nursery, and the types of people he employs – not for wages, but for food, including daily 2lb of bread (‘the very best bread I ever tasted’), half a pound of Cheshire cheese, and 2lb of mutton or pork, ‘taking the whole sheep or the whole pig promiscuously, but keeping all the heads and feet for myself’. He explains his system over four pages, and them gets down to listing his stock, with directions for the simplest way of ordering (by catalogue number x quantity required: so that 93 x 100 would get you 100 tulip trees for 10 shillings – a lovely idea, if you were a gentleman with a large enough estate).

Liriondendron tulipifera in flower.

Cobbett writes at least one paragraph, usually more, about the nature of the tree he is offering, and the reason for its (low) price, and sometimes gives helpful hints on plant care. But he can’t resist a spot of political polemic. The red cedar (Juniperis [sic] virginiana) ‘took its name from that most chaste creature, “good old BETSEY”, who used to hang her loving subjects if they refused to be evidence against themselves, before her High Court of Ecclesiastical Commissioners, and who used to make their bodies, sometimes longer and sometimes shorter, by the rack…’.

Juniperus virginiana with its purple fruit.

He sells catalpa trees for 3 shillings the hundred: ‘no nurseryman can or ought to sell them under a shilling a piece, if for so little; my object is to make the thing general; and to make it general it must be sold at a cheap price’.

Catalpa bignoides in flower.

Among the shrubs on offer are the staff-tree (Celastrus scandens, now commonly called ‘American bittersweet’), for fourpence each: however, ‘I do not know anything about it’. He also has the ‘Judas-Tree (Cercis)’, presumably Cercis siliquastris or canadensis, for the same price.

Celastrus scandens in fruit.

Cercis siliquastrum in flower.

The dog-wood (Cornus florida) provokes mixed emotions. ‘I have formerly said enough about this very early and beautiful shrub, which would be in full bloom here in the month of March. A mortally troublesome fellow, coming up in the second year, just soon enough for our frosts to give it a nip. I thus lost full five-sixths of mine this year. Those that remain are very fine plants, and their leaves, as red as blood, are yet hanging on them.’ Yours, again, for fourpence.

Cornus florida – worth the trouble …

Cobbett offers 57 types of apple tree, including 13 varieties specified as for cider-making. (I must cross-check his list with Robert Hogg’s.) He also has asparagus plants at 2s 6d per hundred, and very trenchant views about how to grow them: ‘gardeners … would make one believe, that they are not to be gotten, except by a sort of conjuration’; whereas his own experience is that benign neglect, rather than endless trenching and mulching, is the way forward, and the reason why asparagus shoots are much bigger in the U.S. than in Britain.

Keen’s Seedling, from vol. 2 of John Lindley’s Pomological Magazine, 1829.

Finally, after two types of strawberry (‘the Keen’s Seedling and the Hautbois’), a hint of seeds, ‘arrived from America this fall. Indeed they are now in the Thames, and I expect them in a day or two. But I expect a great many more, and will therefore not make my catalogue before they arrive.’ The booklet ends with a repeated instruction about the placing of orders, ‘and that the directions for sending the parcels be given as plainly and fully as possible’.

Cobbett’s output continued to be prodigious – he continued to run the nursery, publish the Political Register and books, including The American Gardener (1821); the fascinating Cottage Economy (1821–2), which explained to the country labourer how to grow his own food; and his most famous work, Rural Rides (1822–6), which was intended to reveal to the metropolitan ruling class the actual state of the agricultural counties of southern England. He became an M.P. (for Oldham in Lancashire) in the Reform Parliament of 1833 (having the previous year taken on a farm of 130 acres in Surrey): when he died in 1835 (leaving an unhappy wife and seven children), his estate was (again) bankrupt.

Cobbett’s gravestone, in St Andrew’s churchyard, Farnham.

It would be interesting to know how many gentlemen took advantage of his ridiculously low prices for trees, and whether any of them still flourish today?

Caroline

Pingback: Lucca | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Whilst drafting an article on William Cobbett for Hortus (a literary garden periodical), I came across your excellent blog that sets an impossibly high bar to clear for this unlettered retired professional horticulturist. Had you thought of approaching David Wheeler of Hortus with a view to publication? Though perhaps a little incendiary for some, Cobbett’s obvious literary and horticultural interest as well as intermittent American residencies otherwise hits the Hortus demographic very exactly. Though we know David Wheeler quite well, he is thus far unaware of my ambition to write said article, so the field is clear! And Cobbett deserves the best possible introduction to a modern audience!

LikeLike

Thank you, you are far too kind – I’m always waiting for my rank amateurism to be found out! I know Hortus, of course, but I had never thought of offering the piece for wider publication …

LikeLike

Caroline: Give it a go! Signing off as Professor Hedgehog would very much follow in the footsteps of Cobbett’s ‘Peter Porcupine’. It’s obviously meant to happen!

LikeLiked by 1 person

great article! I am researching George Glenny, editor of the Gardeners gazette and his links to Chartists. Really useful detail here. thank you. keep writing. x

LikeLike

Thank you very much!

LikeLike

My main concern would be the images: they are of course all lo-res, so unsuitable for printing …

LikeLike

Caroline: The Hortus format is very much word based; only B&W images used if at all. As most if not all Hortus readers would be familiar with the species illustrated by colour plates, I guess they would not be missed, though not my place to say. By the way, with regard to the closing question of your blog, you are probably already aware that in Rural Rides Cobbett mentions calling by Coleshill, Oxfordshire (then Berks, I believe) with regard to Locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) trees previously sold to the then owner. Somewhere in my recent research I also noted that he called by a landowner in Scotland to whom he had previously sold a lot of apple trees (American varieties, from memory), and described the crop in predictably effusive terms. At least 2 Cobbett customers. I must stop! I have a Cobbett-like enthusiasm for Cobbett, even re-tracing one of his rural rides. Distilling this down to one article is probably the main difficulty. You are much better placed…..

LikeLike