I have mentioned before Dr Richard Pulteney (1730–1801), the sole survivor of eleven children from an Old Anabaptist family near Loughborough, Leicestershire, who was apprenticed to an apothecary and then set up as an apothecary and surgeon in Leicester. After various vicissitudes (partly caused by potential patients being put off by his dissenting background), he settled in 1765 in Blandford Forum, Dorset, where he became a popular physician, though he never ceased to regret that he could not devote all his time to botany.

He knew almost everyone working in the field of natural history in the period, from the duchess of Portland to Sir J.E. Smith, William Watson to John Martyn, and carried on a voluminous correspondence on his enthusiasms, especially for plants and shells. However, his greatest claim to fame is that he introduced the ideas of Linnaeus to the British public, in his work A General View of the Writings of Linnaeus (1782). In 1790 he published in two volumes Historical and Biographical Sketches of the Progress of Botany in England, which is where I came across William Turner, M.A., naturalist and religious controversialist, as the ODNB has it.

A memorial plaque to Turner at Morpeth.

A tanner’s son from Morpeth in Northumberland, Turner was born in 1509 or 1510. He had somehow come to the attention of Thomas, Baron Wentworth (1501-51), who apparently sponsored him from 1526 with a ‘yearly exhibition’ at Pembroke Hall, Cambridge.

Pembroke Hall (now College), Cambridge – the oldest surviving gatehouse in Cambridge, apparently.

Wentworth was a reformer, and as Turner proceeded through the academic hierarchy (fellow of Pembroke 1531, junior treasurer 1532, M.A. 1533, senior treasurer 1538) his friends included Bishops Latimer and Ridley, at a time when having such friends was dangerous. But he clearly crossed a serious line when, having been ordained deacon in 1536, he married Jane Alder, the daughter of a Cambridge alderman, in November 1540.

Almost certainly not by coincidence, he left the country (probably with his wife) in February 1541, ostensibly to study medicine abroad. He settled at Ferrara, a small hotbed of Protestant exiles, though his M.D. degree was probably obtained at Bologna, where he also heard Luca Ghini lecture on botany.

Luca Ghini, professor at Bologna, and later first curator of the Botanic Garden at Pisa.

After about a year in Italy he travelled north again, and in Zürich ( a very large hotbed of Protestantism) he met the famous naturalist Conrad Gesner.

Conrad Gesner (1516–65), by Tobias Stimmer. (Credit: Museum zu Allerheiligen, Schaffhausen)

The rest of his life (return to England as physician to Protector Somerset, becoming dean of Wells, ordination (finally) by Ridley, exile again under Mary, physician to the (Protestant) earl of Emden (in Frisia), back to Wells again under Elizabeth, the vestiarian controversy, the religious polemics, the translations of Protestant theological works) need, as they say, not detain us (especially the vestiarian part): it is Pulteney’s ringing declaration that ‘the true Era of Botany in England must commence with Dr William Turner’ that I want to focus on.

The memorial plaque to William Turner at Wells.

Pulteney’s book begins with ‘Primaeval Botany’ – i.e. that of the Druids and the Saxons, using Caesar and Pliny as his sources for the former, and decrying the ‘grossest superstition’ which dictated that, for example, mistletoe must be cut with a golden knife. The medieval period was not much better, though he does lists the medieval manuscripts on herbalism and botany that he has found, both in Oxford and Cambridge college libraries and in the collection of Sir Hans Sloane. Even the Grete Herball of 1526, compiled from continental sources and printed in Southwark by Peter Treveris, was, according to Turner himself, ‘full of unlearned cacographees, and falsely naming of herbs’.

Title page of The Grete Herball. (It may have been first published in 1516, but if so there are no surviving copies.)

(Turner defends his own decision to write in English, for a very practical reason: ‘How many surgianes and apothecaries are there in England, which can understand Plini in Latin or Galene and Dioscorides, where as they wryte ether in Greke or translated into Latin’.)

Once resettled in England, Turner ‘seems to have divided him time between his deanery, where he had a botanical garden … and his house in Crutched Friers [sic], London’, where he died in 1568. (There is also mention of another garden, at Kew.) His first notable book was Names of Herbes, in Greek, Latin, English, Dutch, and French, published in 1548. (Pulteney notes that this work is now very scarce, ‘since it has not yet found its way into the copious and magnificent collection of Sir Joseph Banks’.)

Turner also wrote on birds (he has a claim to be ‘the father of British ornithology’) and supplied Gesner with a paper on English fishes (which was later published in the third volume of the 1620 edition of the latter’s Historia Animalium), and elsewhere noted his intention of making a fuller study: ‘to set out a book of the names and natures of the fishes of her majesty’s realms’. But, as Pulteney says, ‘the work which secured his reputation to posterity, and entitled him to the character of an original writer on that subject, in England, is his “History of Plants”’, or New Herball.

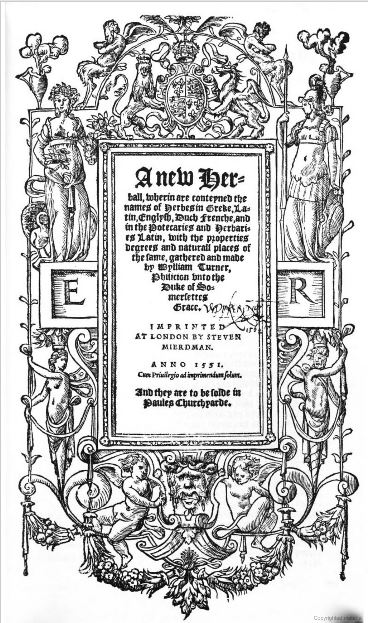

The title page of the first volume of Turner’s New Herball.

The first volume was printed in London in 1551, the second in Cologne in 1562, during Turner’s Marian exile, together with a reprint of volume 1 and a ‘Book on the Bathes of England and Germany’. (He also wrote a book on the nature and virtues of triacle, i.e. theriaca.) The third volume came out in England a few months before his death in 1568, but had been printed in Cologne in 1566, and the dedication page, to the Surgeons’ Company, was dated from Wells in 1564.

Turner’s description of ‘scorpion’s tail’, or Heliotropion. He pours scorn on the ‘unlerned selfe made Phisicians whiche teache you to call a Marigolde Heliotropion’.

The scorpion’s tail, Heliotropium angiospermum.

Turner’s great virtue, according to Pulteney, was that ‘he nowhere takes any doubtful plants upon trust’ but appears to have examined them with all the precision usually exercised at a time when method, and principles now established, were unthought of’. He also ‘first gave names to many English plants; and, allowing for the time when special distinctions were not established, when almost all the small plants were disregarded, and the Cryptogamia almost wholly overlooked, the number he was acquainted with, is much beyond what could easily have been imagined, in an original writer on his subject’.

Cassia fistula, the golden shower tree.

In the final part of the herbal, he deals with plants ‘not known to Dioscorides and the antients’, many of which came from the East and the West: ‘such as cassia fistula, cubebs, guaiacum, nutmegs, myrobalans, nux indica, nux vomica, anacardium, rhubarb, sarsaparilla, senna, and tamarinds’, for which new woodcuts were made.

The reason for the third volume being printed in Cologne, and the time from writing to printing, is probably accounted for by the German printer holding the woodcuts for the earlier volumes. ‘They are the same with which the octavo edition of Fuchsius was first printed in 1545’, which is a nice irony given that Turner ‘bestows much criticism on the commentaries of Fuchsius, Tragus, Matthiolus, and other of his contemporaries’, for their heedless adoption of ancient names from the eastern Mediterranean for the plants of north-western Europe.

The hiacinthus, with proposed English names. Note the references to Luca Ghini of Bonony (Bologna) and ‘Mount Appennine’.

Woodcuts of the hiacinthus.

Among the plants Turner suggested English names for are: Aconitum, ‘monkshood’ (from the German); Lonchitis aspera, ‘combe-ferne’ (because it is a fern and it looks like a comb); Amara dulcis (now Solanum dulcamara), ‘bitter-sweet’; Euonymus europaeus, ‘spindle-tree’ (from the Dutch); Lysimachia vulgaris, ‘loosestrife’ (from the Greek ‘release from war’); . Two which did not last were ‘crowfoot’ instead of bluebell for Hyacinthus, and ‘calf’s-snout’ for Antirrhinum.

Two flowers of the genus Turnera: above, Turnera subulata, named by Sir J.E. Smith; below, Turnera ulmifolia, named by Linnaeus. Of the passion flower family, they come from South America and the Caribbean.

Turner’s pioneering work was used by later herbalists and botanists, including John Gerard, and John Parkinson, but Pulteney clearly thinks they do not give him enough credit. John Ray, however, ‘was sensible of his worth, having stiled him “a man of solid erudition and judgment”’ – and who are we to disagree with Ray? Moreover, he has his own genus, the Turnera, given to him by Plumier, but first discovered by Sloane in Jamaica.

Caroline

Pingback: The Naming of Plants | Professor Hedgehog's Journal

Pingback: The Bluetit | Professor Hedgehog's Journal