One of the upsides of the lockdown (from my own purely selfish point of view) is that I have been able to spend much more time watching the birds in my garden, at a time of year when they are of course at their most active. Many people have commented on the joy of hearing birdsong without the constant background rumble of traffic: at the moment, a local blackbird sits in a tree overhanging the garden and kicks off at about 4 a.m. (or so I am told by Him Indoors, who says he wakes him up) continuing on and off throughout the day and even after dusk.

One of the upsides of the lockdown (from my own purely selfish point of view) is that I have been able to spend much more time watching the birds in my garden, at a time of year when they are of course at their most active. Many people have commented on the joy of hearing birdsong without the constant background rumble of traffic: at the moment, a local blackbird sits in a tree overhanging the garden and kicks off at about 4 a.m. (or so I am told by Him Indoors, who says he wakes him up) continuing on and off throughout the day and even after dusk.

However, the most frequent visitors to the garden are (now as always) the bluetits, and the surrounding quiet has made me appreciate quite how varied their calls and ‘singing’ are: I keep thinking that something new and exotic has arrived, but when I can locate the source of the sound, I realise that it’s ‘just another’ bluetit.

Does anyone remember ‘Swoop’ birdfood in the 1950s (which we bought from the greengrocer)?

As well as ‘Swoop’, we fed the birds with hanging coconut halves and threads of peanuts, which were also bought at the greengrocers, labelled ‘not fit for human consumption’. This painting was a present to me from my daughter when she was at primary school.

It once had a competition in which one had to write an essay on the most interesting bird that had visited one’s bird table. I wrote on the bluetit, and sent the essay in – never heard another word about it, needless to say, but it confirmed a love affair with this delightful little object which has lasted considerably more than half a century. (I do have to confess, though, that I switched half my allegiance to the long-tailed tit the first time I ever saw one …)

The bluetit, by Thomas Bewick.

Thomas Bewick’s engraving of the bluetit (which he names ‘The Blue Titmouse, Tomtit, Blue-cap or Nun’ in his History of British Birds, Vol. 1, 1797), naturally, nails it. (A few other vernacular names, incidentally, are elicompanie, wagstert, betty-tit, heckemal, pinchem, jenny-tit, billy-biter and archangel.) More or less accurate images of the bird are fairly common in medieval manuscripts,

This immediately recognisable bird perches in MS Royal 3 D.VI, f. 116. (Credit: the British Library)

but it was from the end of the nineteenth century and the rise in appreciation of and concern for our native birds that the depiction of bluetits as decorative objects – in paintings, prints, embroidery, sculpture, greeting cards, stained glass, mugs, coasters, tea towels, etc., etc. – really took off.

Wallpaper by Morris and Co., 1926, with a bluetit attacking a pomegranate.

My bluetit tea towel.

Incidentally, the (now Royal) Society for the Protection of Birds was founded in Manchester in 1889, merging in 1891 with the ‘Fur, Fin and Feather Folk’, who were based in London.

A spectacularly distasteful hat, ‘ornamented’ with a bird of paradise, from the late Victorian period. (Credit: Popular Science)

Originally a ladies-only group, the SPB’s intentions were to ‘discourage the wanton destruction of birds and interest themselves generally in their protection’ and to ‘refrain from wearing the feathers of any bird not killed for purposes of food, the ostrich only excepted’. (Was the ostrich excepted because of its association with presentations at court, or because in South African ostrich farms, the plumage was harvested every 6–8 months, without (much) harming the birds?)

This image of the bluetits (and an egg) in The Ladybird Book of Birds and Their Nests is, in my view, rather more successful than that of the robin, though it doesn’t quite capture the bumble-bee-like fuzziness of the babies as they queue up to be fed.

The bluetit, its family, and its egg, from The Ladybird Book of Birds and Their Nests.

One of the features which this and other bird books of the 1950s always mention is that the bluetit will, given half the chance, peck through the foil top of the milk bottle on your doorstep and suck up the cream on the top.

In another Ladybird book, the ‘natural’ food of the notoriously carnivorous raven seems to include an apple, the kingfisher has a fish, and the bluetit drinks milk.

We experienced this learned behaviour (first observed in the 1920s) when I was young; I remember my mother acquiring two rather lovely terracotta bottle holders with close-fitting lids, which not only thwarted the birds but could also hold cold water to keep the milk cool in a shady spot, since we didn’t have a refrigerator. (Yes, dear reader, I really am that old.)

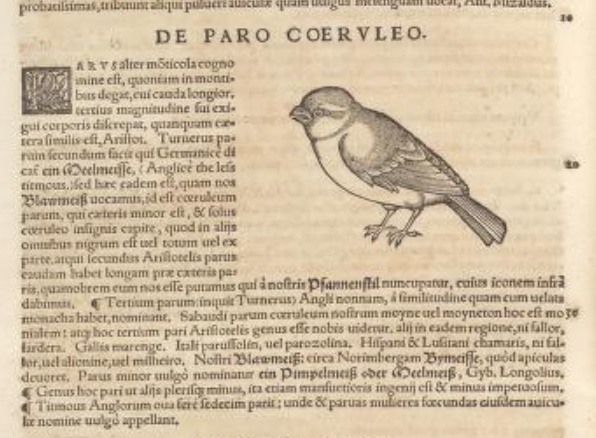

The taxonomy of the tits used to be relatively straightforward. The bluetit was Parus caeruleus (Linnaeus in 1758 adopted Gesner’s 1555 name), parus being the Latin for ‘bluetit’ and caeruleus meaning ‘sky-blue’.

Gesner’s bluetit, from his Historia Animalium, vol. 3, of 1555. The last lines read: ‘The ‘titmous’ of the English, it generally lays sixteen eggs [!!!]: thence some fertile women are commonly called by the name of this little bird.’

I can’t resist putting Bewick’s long-tailed tit in here, though it’s not very relevant.

And the bluetit itself has not been immune to change of nomenclature. In 2005, Parus caeruleus suddenly became Cyanistes caeruleus, as a result of DNA analysis that distanced it from the Parus family and linked it to the African bluetit (C. teneriffae), found in north Africa and the Canary Islands, and named in 1831 by René Primavère Lesson (1794–1849), a naval surgeon and naturalist who was an associate of Dumont d’Urville. Cynanistes means ‘dark blue’ (Greek κύανος, used of lapis lazuli, the blue cornflower and the (Mediterranean) sea: the African bluetit, though similar in many ways, does have a much darker head than the European.

Cyanistes teneriffae, showing a darker head.

According to the RSPB, there are 15 million bluetits in the UK, and anything between 40 and 88 million in Europe: their UK conservation status is (unsurprisingly) green, and their position on the IUCN Red List is among ‘least concern species’. They eat insects, caterpillars and seeds, and usually lay 7–8 (rather than 16) eggs in a nest of moss, twigs, feathers and wool scraps. They are the birds most likely to nest in a human-provided box, but use all sorts of holes and crevices, including this street light near Ropemaker’s Field in Limehouse.

I am ridiculously proud of this picture. I had watched the adult birds flicking rapidly in and out of the hole for some time, and eventually just pointed my camera at it and took a burst of pictures. To my complete astonishment, I caught this view.

Both adult birds feed their young, first inside the nest and later, usually, as they line up in a row of gaping beaks on a branch or a fence. The adults are almost literally run (flown) ragged by the end of the breeding season, when their plumage becomes dull and scruffy from sheer exertion and exhaustion. Their average lifespan is about three years, though only about a third of the fledglings survive their first year.

Philadelphus ‘Belle Etoile’. The wretched blackfly attack when the flower buds are tiny, engulfing and sucking the life out of them. (Credit: J.Parkers)

The only problem I have with these delightful birds is a small one: why don’t they eat the blackfly which are (already!) attacking the shoot-tips of my Philadelphus ‘Belle Etoile’. Is this how they reward me for spending a small fortune on sunflower seed kernels for their delectation?

Caroline

All fascinating and sheer pleasure, words and pictures.

LikeLike

Thanks – you’re very kind!

LikeLike

Wonderful journey entry and great lucky photo…thanks for writing.

LikeLike

That’s very kind of you, thanks! The bluetit in the lamp-post was photographed almost exactly a year ago, when one could wander round the streets at will … All good wishes, Caroline

LikeLike

Pingback: The Pliny of Switzerland | Professor Hedgehog's Journal