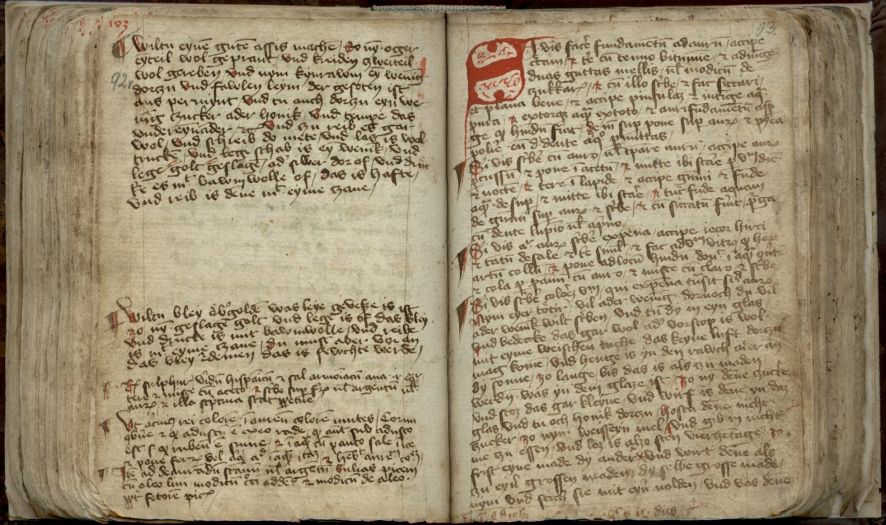

A bit more about how everything is in fact connected to everything else … I first came across Mary Philadelphia Merrifield (née Watkins: 1804–89) early in 2016, when I was trying to find out about Armenian bole, and regretted that back in the day we had not reissued her works on art (mostly of the Italian Renaissance), which began with her 1844 translation of l libro dell’arte, which basically told you how to paint. Written by Cennino di Andrea Cennini (c. 1360 – before 1427), a pupil of Gaddi, who was a pupil of Giotto, it was rediscovered and published in Italian only in 1821.

The other week, colleagues were discussing the correspondence (held in the archives of the University of Cambridge Herbarium) of a Mrs Merrifield with Charles Cardale Babington, botanist and former Director of Cambridge University Botanic Garden, and many others. ‘Oh,’ I said, ‘I wonder if she was related to the Mrs Merrifield who wrote about art?’ On looking her up, I found that she was so closely related that she was the same person (in fact I now realise that I knew this already but had forgotten it, increasingly the story of my life), and not only that, but that she spent the latter part of her life in Stapleford, near Cambridge, where her son-in-law was the vicar.

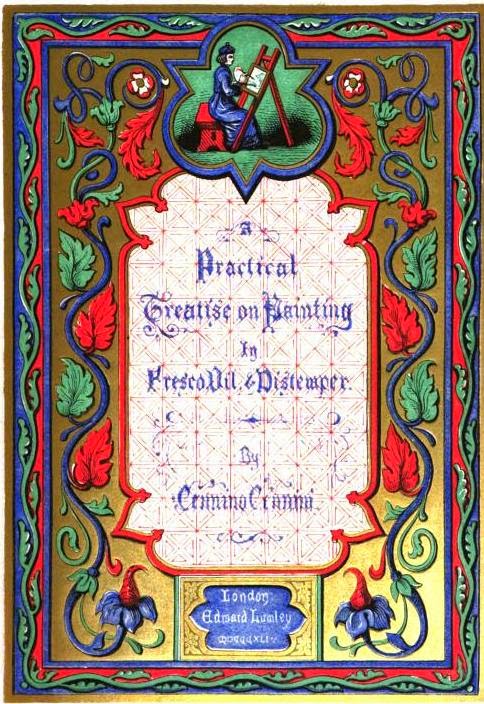

Mary Philadephia Watkins was born in London, the daughter of a barrister, and in 1827 she married another barrister and went to live in Brighton. Her translation of Cennino, published as A Treatise of Painting, demonstrates her level of education, about which, sadly, nothing seems to be known, but which was clearly considerable. As a result of this work, she was asked by the Fine Arts Commission (which had been established in 1841 at the behest of Prince Albert to oversee the decoration of the new Houses of Parliament after the fire of 1834: the post of President was the Prince Consort’s first official role in Britain) to investigate the history of painters’ materials and techniques.

This resulted in The Art of Fresco Painting, as Practised by the old Italian and Spanish Masters, with a Preliminary Enquiry into the Nature of the Colours Used in Fresco Painting, with Observations and Notes. It was published in 1846, and was dedicated to Sir Robert Peel, as was her next work, Original Treatises Dating from the Twelfth to the Eighteenth Centuries, on the Arts of Painting in Oil, Miniature, Mosaic, and on Glass; of Gilding, Dyeing, and the Preparation of Colours and Artificial Gems; Preceded by a General Introduction; with Translations, Prefaces and Notes. This was published (in two volumes) in 1849 by John Murray. (A Treatise of Painting had been published by the rather less well known Edward Lumley of Chancery Lane, and The Art of Fresco Painting was published ‘for the author’ in London and Brighton.)

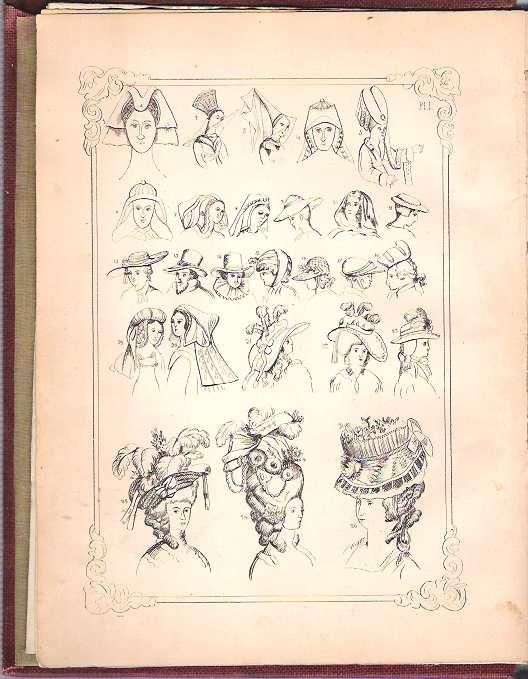

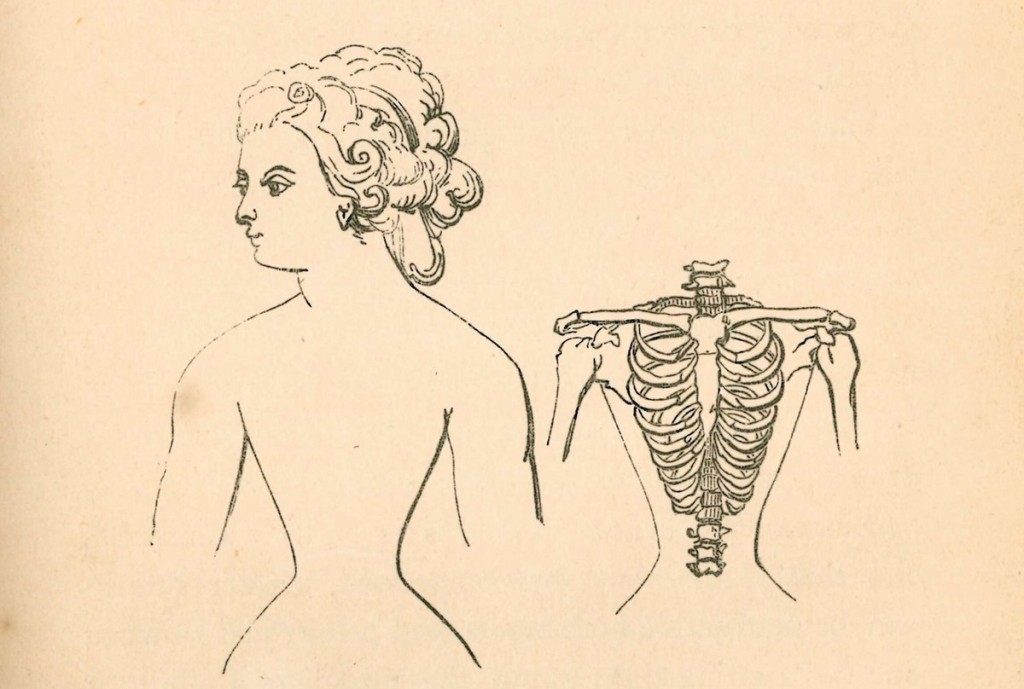

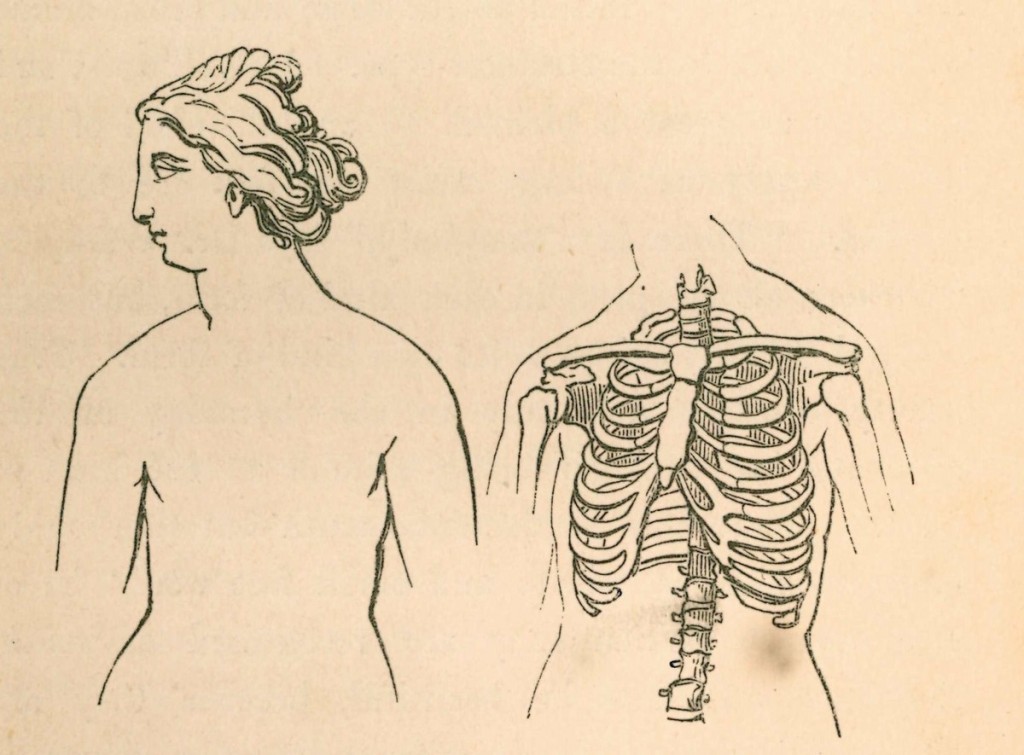

In 1851 followed Practical Directions for Portrait-Painting in Watercolours, published by Windsor and Newton, ‘Artists’ Colour Makers, by Special Appointment, to Her Majesty and to H.R.H. Prince Albert’, and in 1854 Dress as a Fine Art, a collection of articles on fashion which she had published in various women’s magazines. Her last work purely on art, A Handbook of Light and Shade with Reference to Model Drawing, was published in 1855.

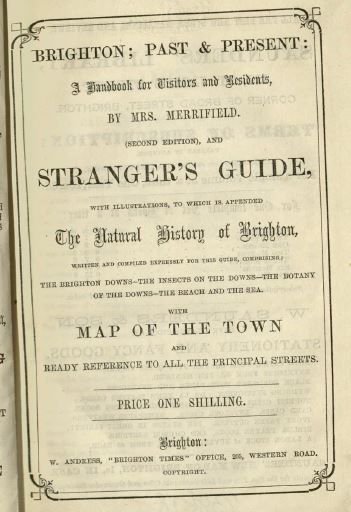

Once settled in 2 Dorset Gardens, Brighton (which seems to have been demolished and rebuilt as flats fairly recently), she produced a guidebook, Brighton Past and Present (1857), and in 1864 A Sketch of the Natural History of Brighton.

In 1857, she was given a civil list pension of £100 as an acknowledgement of her services to art and literature. Meanwhile, she was raising three children – Charles, Frederick and Emily.

Charles (1827–84), having started out studying law like his father, decided to move sideways to his favourite leisure pursuit, mathematics, and became a well-respected teacher (it is suggested by the ODNB that A Handbook of Light and Shade was written at his urging to assist in art education), Fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1864, Principal of the new Royal School of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering at South Kensington. He belonged to dozens of mathematical societies and published dozens of articles on mathematics and education more generally, as well as at least ten books. Like his mother, he was fluent in several languages.

Frederick (1831–1924) did become a lawyer, but was also a keen entomologist, researching in particular on the effect of different temperatures during pupation on the colours of the adult butterfly. He was also a vigorous supporter of women’s suffrage, and a spiritualist – though he was one of the many who were sceptical about the Scots/American medium Daniel Dunglas Home.

Rather less is known about her daughter Emily (and I have not been able to find an image of her), except that she married the Reverend Charles Henry Thomas Wyer Daw (1832–98), a Devon man who had studied at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, before ordination and a chaplaincy at Ely. Between 1861 and 1872 he was rector of Otterham, Cornwall, and moved to Stapleford in 1872, serving as its rector until his death.

John Merrifield having died in 1877, Mary Philadelphia moved to be with her daughter in Stapleford. The vicarage there had been newly built by her son-in-law, out of concrete, which must have been fairly startling for the inhabitants of this quiet village: see this account for more details about Revd Daw.

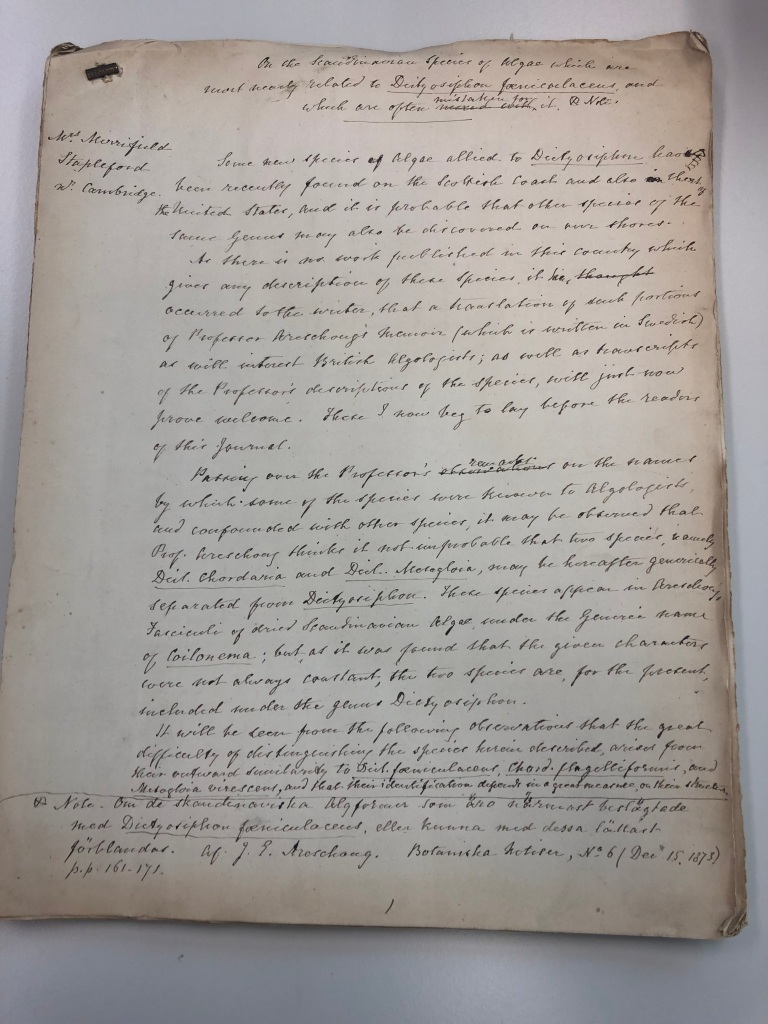

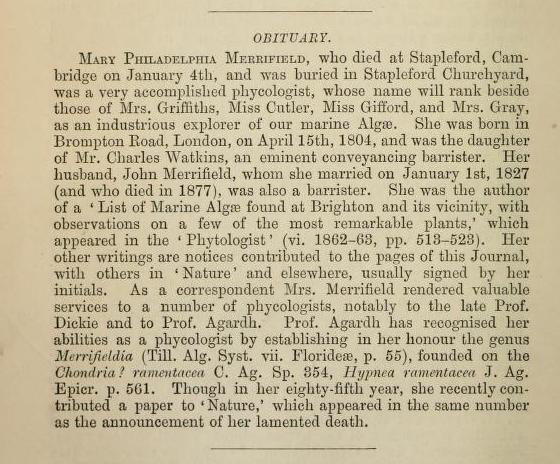

I wondered whether Mrs Merrifield had already been in correspondence with Babington while she was still in Brighton, or whether she met him first in Cambridge and discovered their mutual interest at that point. Since she published on algology in the Journal of the Linnean Society, the Journal of Botany, and the Annals of Botany, as well as in Nature, it seems likely that he would have been aware of her work.

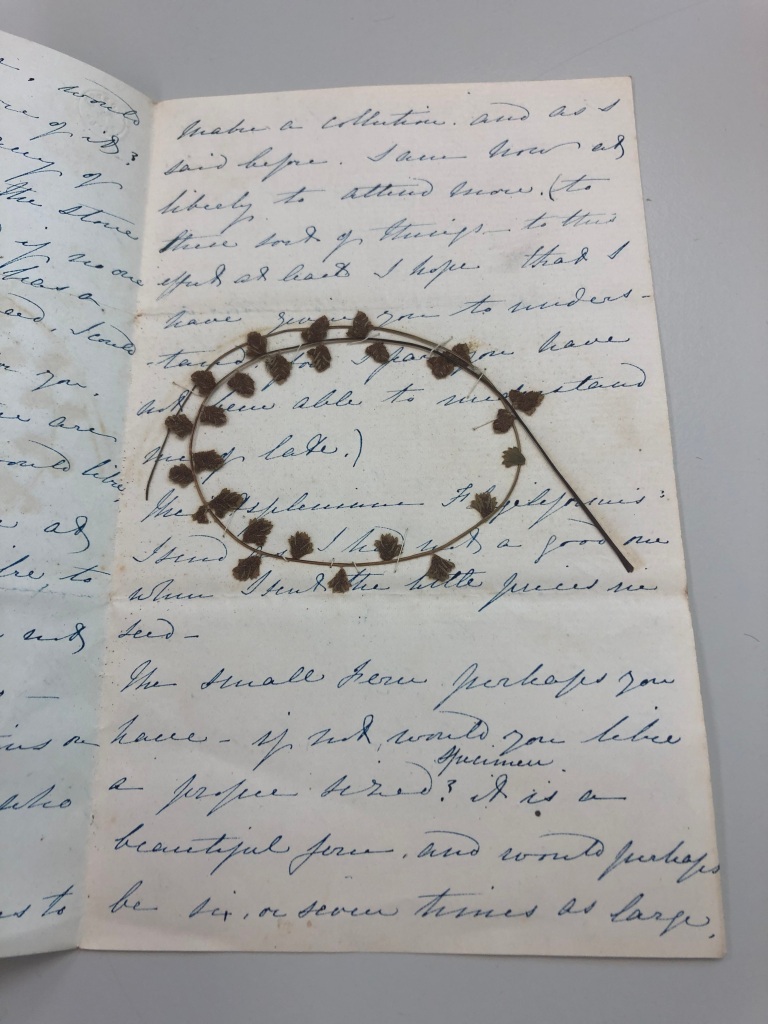

Happily, I was recently given access to the Merrifield archives in the Cambridge University Herbarium, apparently donated by her daughter after her death. They consist partly of letters to Mrs M. from the botanical great and good, and from other ‘amateur’ enthusiasts, and partly of folders of notes on seaweeds, reviews of books, and draft articles of her own.

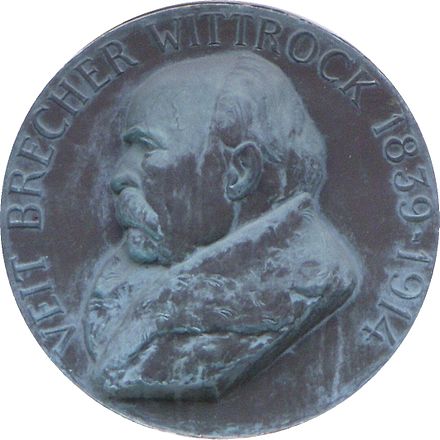

Her correspondence was worldwide. She received letters from, for example, the Swedish botanist Veit Brecher Wittrock (1839–1914) who as well as studying seaweeds was an expert on the genus Viola, and had the genus Wittrockia (Bromeliads) and the green algae Wittrockiella named after him.

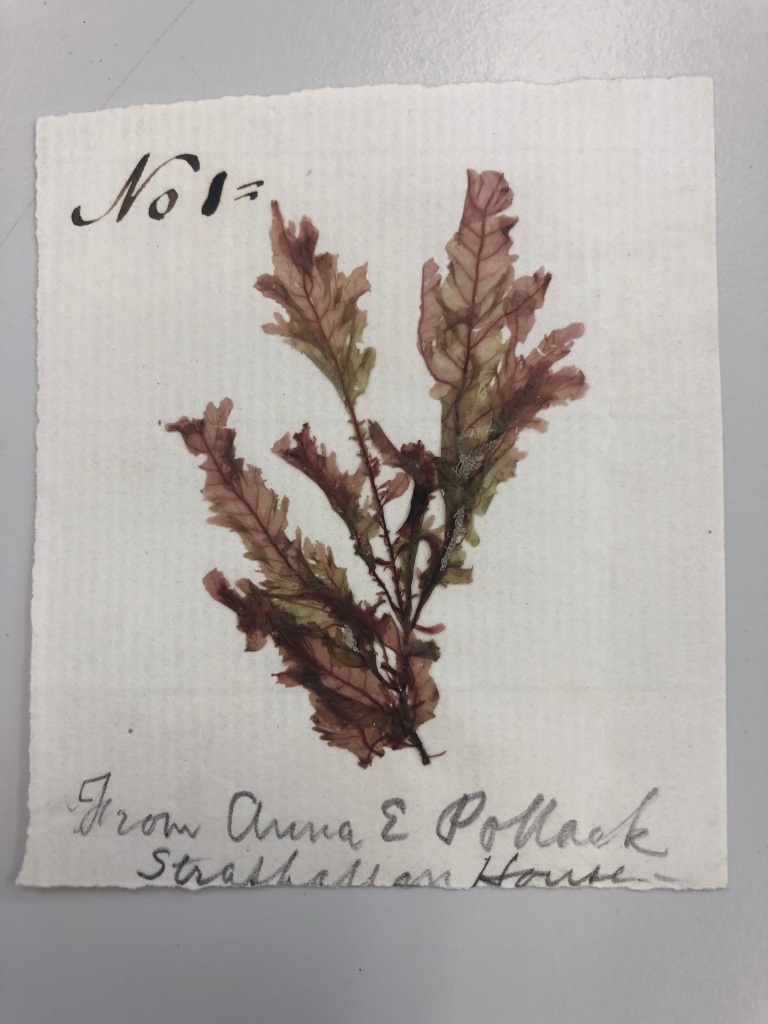

Another Swedish correspondent was Jacob Georg Agardh (1813–1901), son of the possible more famous Carl Adolph Agardh (1785–1859), who was a pioneering algologist and also bishop of Karlstad. One Allen Y. Moore of Coldwater, Michigan, USA, sent her four specimens of seaweed, and asked for some to be sent in exchange, while a letter from an Anna Pollock, who was staying at Strathallan House (possibly the one in Stirling???) contained a pressed plant and a piece of seaweed, neatly labelled. (Miss Pollock describes her pastime as ‘seaweeding’.)

Somebody with a (to me) illegible signature, writing from Kew, assured her that her specimens of Griffithsia barbata (named in 1828 by the said Carl Adolph Agardh, but now a synonym of Anotrichium barbatum (bearded red seaweed)) had been gratefully received by Sir William Hooker as a donation to the Kew Herbarium. Another, from Joseph Dalton Hooker, refers to a letter of hers which is to be read at the next meeting of the Linnean Society.

More prosaic messages include several from ‘Printers, Red Lion Square, London’ asking her to mark and return proofs, or to supply photographs for the Linnean Society; and there is a letter asking a friend to show ‘little Alice’, the daughter of another friend, how to dry seaweed. There is also a request to the Museum of Practical Geology, Jermyn Street, London (who knew?), asking for a sample of websterite (now known as aluminite).

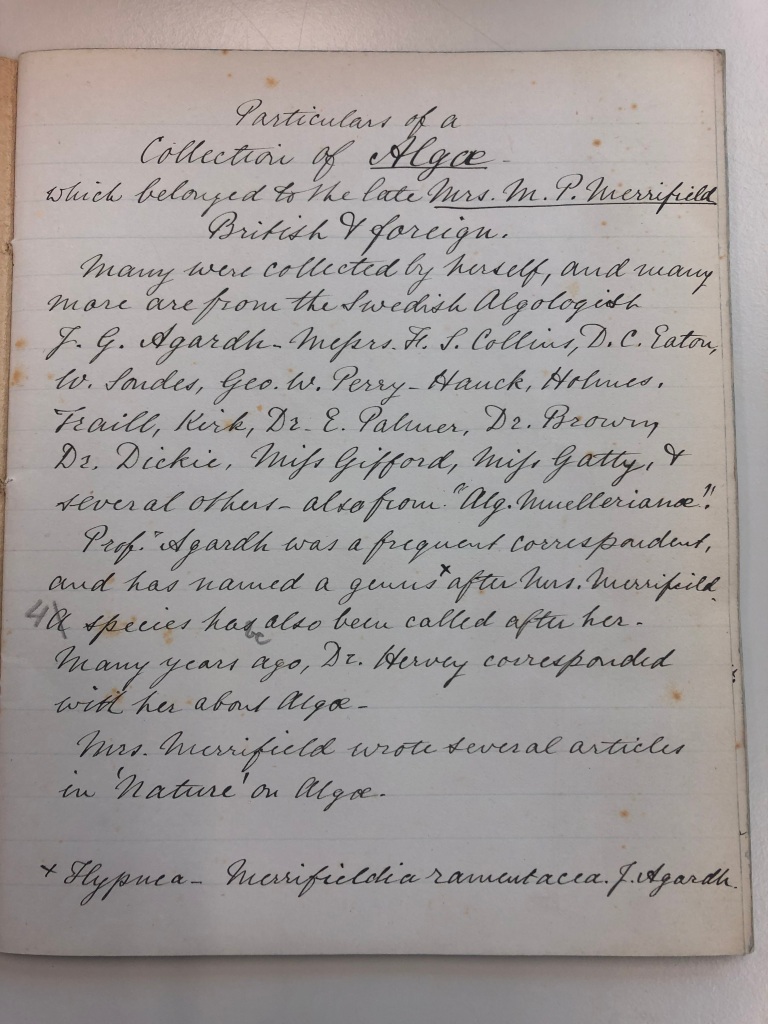

One of the folders (above) consists of a list of the ‘Collection of Algae which belonged to the late Mrs M.P Merrifield, British and foreign. Many were collected by herself …’.

J.G. Agardh is mentioned as a contributor to the collection, and also as the namer of the genus Merrifieldia in her honour (though sadly this appears not to have stood the test of time either). The page says that ‘A species has also been called after her’, but this has been corrected by pencil to read ‘4 species have …’, but the only Merrifieldia that I can find is a genus of moths named by one James William Tutt (1858–1911), so that, as so often in matters of taxonomy, I am confused. The collection itself, of over 6,000 specimens, is now in the Natural History Museum, London.

Other items in the archive are abstracts of published articles by others, and apparently draft writings of her own, some of them in French and German. They consist of several hundred pages of closely written neat text, with the occasional illustration, and are evidence of the hard work which she clearly put in all her life to her studies whether of art or of algology. I was delighted to learn that the archive is currently being studied in the detail which it clearly deserves in an upcoming dissertation.

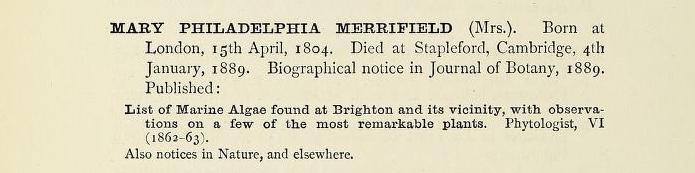

I had assumed that Mrs Merrifield, when she died in Stapleford at the age of 84, would have been buried in the churchyard there, but neither the vicar nor the local history society knew of her grave, and I began to wonder if her body had been sent back to Brighton for burial, especially after I had spent a hot afternoon in the churchyard and adjoining cemetery trying to decipher names on the lichened-over or eroded tombstones. However, while looking for obituaries, I found one in the Journal of Botany for 1889 that states categorically that she is there, somewhere. I shall have to go back and try again.

Caroline

She was a wonderful woman by the sound of it and her achievements should be marked, perhaps at the Botanic Gardens. I could do with some of her advice on light and shade!

LikeLike

Thanks, Paula, I agree!

LikeLike