No, we haven’t been to Crete after all our other recent jollies, merely (sic) to Oxford, to see the Ashmolean exhibition ‘Labyrinth: Knossos, Myth and Reality’. I have mentioned a few times recently the problem that I am having with my brain, but it was only when we were having lunch in the fourth-floor restaurant before going in that I realised that it is almost exactly fifty years since I last visited Knossos. (Disclaimer: I was about to write that we have been to Crete once since then, but more for a beach holiday with the children than for serious stuff; however my daughter informs me that she remembers going to Knossos, and that we went to hardly any beaches …)

Given that the study of the Minoans and Mycenaeans was a full-time activity for me for as many years as it took me to realise that I had no serious chance of an academic career, I was pleased to discover that I hadn’t forgotten everything I ever knew about Knossos – I had even remembered that the first serious exploration of Knossos was carried out by a man called Minos, though I had forgotten that his surname was Kalokairinos (1843–1907).

The son of a businessman from Heraklion, Minos began to study law in Athens, but did not practice, as his father’s illness and subsequent death forced him to return to Crete to take over the family business with his brother. A keen amateur archaeologist, he began to excavate at the site in 1877. However, at this time Crete was still part of the Ottoman Empire, and the Turkish government put a stop to his work in 1878, by which time he had discovered some of the large storage rooms and what later turned out to be part of the ‘Throne Room’.

During the unrest in the Cretan revolt of 1898, Kalokairinos’ house was pillaged and burned down; some of the items which survived were enormous pithoi from the palace. This one, on display in the exhibition, is now held by the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion; he donated another to the British Museum via Thomas B. Sandwith, the British Consul in Crete, in 1884. (In writing to the Museum, Sandwith also referred to clandestine excavations occurring at the site.)

Other archaeologists, including Heinrich Schliemann and Arthur Evans, who in 1884, after several years of journalism and archaeology in eastern Europe and the Mediterranean, was appointed Keeper of the Ashmolean, took a great interest in these findings, and in 1894 Evans succeeded in purchasing part of the site. After the Turks finally left Crete in 1899, he began excavating, and the rest, as the exhibition title indicates, is ‘Knossos, Myth and Reality’ – most especially his controversial reconstructions of ‘the Palace of Minos’ on the site.

His connection with the Ashmolean means that a lot of his own Stuff – diaries, pieces of pottery, maps, seal stones – is now housed by the Museum. I was delighted to see that one of the first objects on display was a copy of Thomas Spratt’s survey map of Crete, Evans’s own, and much used by him, apparently.

I was slightly surprised (I had forgotten they had any) to see two Linear B tablets from the Ashmolean itself on show, though the label didn’t give their standard numbers, which was frustrating, and they were too deep in their glass case for my feeble eyesight to make out the syllabograms.

There was also a stone offering table inscribed in Linear A, which remains undeciphered (in spite of various claims and counter-claims) simply because so few examples of the script have survived.

A fascinating insight into daily life is provided by a crude stone quern and a round stone for grinding grain. The carbonised grain next to it is wheat, but according to the caption: ‘The botanist who first identified these grains refused to publish his report because he could not believe that wheat was being grown on Crete at such an early date – they are still the earliest ever found in Europe.’

There were some spectacular pieces of pottery and sculture, in addition to Kalokairinos’ pithos. Look at this stone shell vessel, for example:

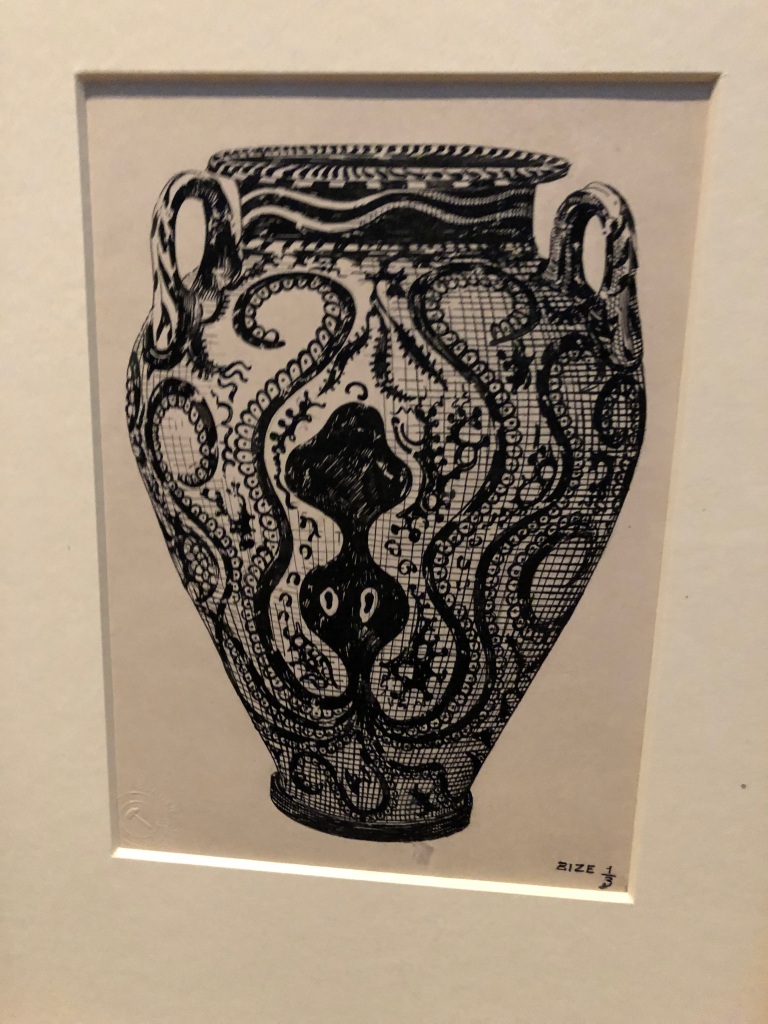

and one of the famous octopus pots, in this case a drawing by one of Evans’s team – perhaps even Evans himself.

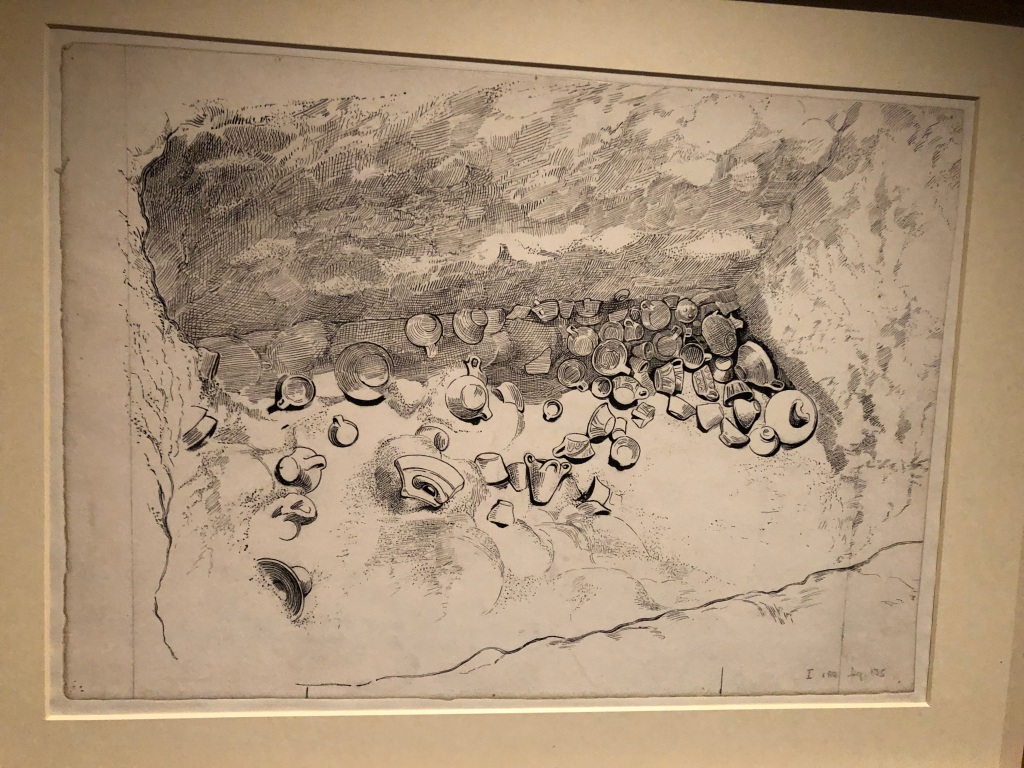

Many of the pots were drawn in situ before being removed, and this recording help Evans to hypothesise the chronological sequence of styles – Early, Middle, and Late Minoan – still in use today.

Halvor Bagge (1866–1939), who drew the pots, also made plaster reproductions of the more famous items, such as the ‘Snake Goddesses’ (below), so that the Ashmolean would have replicas.

The most controversial aspect of Evans’s work was his architectural ‘reconstruction’ of the palace, carried out on the basis of archaeological drawings by his team. The Grand (or Royal) Staircase is seen in this proposed reconstruction by Christian C.T. Doll (1880–1955); iron girders were used instead of wooden beams, and plastered stone instead of wooden columns.

Other items which bring the story up to date include a printing plate for Evans’s The Palace of Minos, published between 1921 and 1936:

and information about more recent excavations elsewhere in Crete. The most spectacular of these is apparent evidence for a human sacrifice which was being carried out in a house on the slopes of Mount Iuktas, but was interrupted, probably by an earthquake, in mid-ritual. The excavators, in 1979, found the body of a man lying on a platform, and those of a man and a woman who were perhaps carrying out the deed. The exhibition suggests that if human sacrifice was in fact a Minoan habit (and apparently other finds elsewhere on Crete may confirm this theory, though many scholars dispute it), it may have given rise to the myth of Theseus and the other Athenian youths and maidens sent to Crete to be killed by the Minotaur.

My favourite item, on purely aesthetic grounds, was this little crocus cup.

Saffron was important in Minoan life, both as a condiment and a dye for cloth, and it is lovely to see it depicted in the domestic context, as well as in the famous ‘Saffron-Gatherer’ frescoes, both on Crete itself and on the island of Santorini.

It is entirely appropriate that the exhibition is being held this year, the platinum jubilee of the confirmation (by means of newly discovered tablets from Pylos in Messenia) that Michael Ventris’s decipherment was correct, and that Linear B is the earliest known form of Greek. The first edition of Ventris and Chadwick’s Documents in Mycenaean Greek, explaining the method of decipherment (a feat widely known as ‘the Everest of archaeology’) and giving translations of the content of many tablets, was published in 1956.

A second edition, by John Chadwick alone, after Ventris’s tragic early death, was published in 1973, and later this year, Cambridge University Press will be publishing the two-volume The New Documents in Mycenaean Greek, edited by Professor J.T. Killen, and containing, as well as much material from the first edition which has stood the test of time, new essays by scholars worldwide on the interpretation of texts that have come to light in more recent years, and further discussion on their context, comparisons with similar documents from Egypt and the Near East, and the insights they bring to bear on the life and society of the Minoan and Mycenaean world. I had the privilege, a few months ago, of reading a set of proofs, and the work (for those who like that sort of thing) is completely stunning. Pre-order your copy now!

Caroline

Blessings on you and your entries. The texts, the images, and your boundless curiosity delight and inspire me, way over here in Portland, Oregon, U.S.A.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for your kind words! The world is just such a fascinating place …

LikeLike

I was so disappointed with Knossos (I went in 1989 I think). I was obsessed with Leonard Cottrell’s ‘The Bull of Minos’ and CW Ceram’s ‘God, Graves & Scholars’ when I was a teenager. When I finally got to Knossos I was a bit shocked to see that the most famous bit of the site was mainly a reconstruction; quite why I hadn’t realised before that ancient ruins don’t come out of the ground with fresh paint on them I don’t know. But Phaistos I loved. And the museum in Heraklion is superb as well. Thank you for reminding me of my long forgotten fascination with the Minoans and Mycenaeans.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment – and I know what you mean about the restorations … Quite agree about Phaistos, though!

LikeLike

Thank you I too remember a visit long ago to Crete and your article brought the memories back.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston had a snake goddess they were very proud of — when I was a student at Boston University in the 1950s. Ivory and gold, as I remember it.

LikeLiked by 1 person