it is almost exactly a year since I last did a ‘Plant of the Month’ post, so I thought I had better get back into that particular delightful harness. In @CUBotanicGarden the other day, I was admiring the way in which the tiny individual flowers of teasels come out in bands around the spiky flower head, and remembering dimly that the ‘ripe’ brown heads were once used in the cloth trade.

The last few years have been brilliant for teasels: they like poor soil, and seem to flourish more in hot summers. At the moment then can be seen in massive numbers along the railway line to London, along with the buddleia, which is again flowering early.

The Linnaean name is Dipsacus fullonum, Dipsacus from the Greek δῐ́ψᾰ, ‘thirst’ (cf. dipsomania), because the leaves create a small ‘goblet’ where they join the stem, in which water collects, and which helps to foil the upward march of aphids. (I find from this article from the website of the invaluable Darwin Correspondence Project that Francis Darwin believed that teasels might be carnivorous, absorbing nutriment from the drowned aphids, but the case seems at present to be non-proven.)

The second half of the name, ‘fullonum’ refers to the teasel heads’ use by fullers, Latin fullones (yes, it’s one of Linnaeus’s appalling Greek/Latin hybrids!), in the preparation of cloth. Famously, the first stage in finishing woven cloth was to pound or trample it in tub of urine, the ammonium in the urine cleansing grease from the cloth and whitening it. (Fullers’ ‘factories’ were frequently required to be established outside of town because of the appalling smell.)

This was called scouring, and after it the cloth had to be rinsed thoroughly in clean water. Once the clean cloth had been stretched and dried on tenterhooks in a tenterground, the nap was raised using the teasel as a comb, originally by placing the seedheads in a small wooden frame and scraping by hand, and later in industrial-sized frames.

Metal combs were introduced in the twentieth century, but apparently some craftspeople still prefer to use teasels, as a metal comb encountering resistance may rip the cloth, whereas the teasel will break and the cloth remain unharmed.

Teasels, which are native to Eurasia and North Africa, must therefore have been grown for this purpose in wool-farming areas, but unfortunately, where it was introduced for the wool trade, e.g. in Australia and New Zealand, it is now classed as a noxious weed.

It is a biennial, and the seed-heads provide useful food in winter, especially for goldfinches.

Its main use today is as an ornamental, ‘architectural’ garden plant, and the branches with dried seed-heads are often used in floristry. Among its common names are ‘Adam’s flannel’ and ‘barber’s brushes’ (the latter slightly more intelligible than the former), ‘church broom’ and ‘prickly back’. It is also known as ‘water thistle’, which seems odd, given that it is usually found flourishing in very dry conditions.

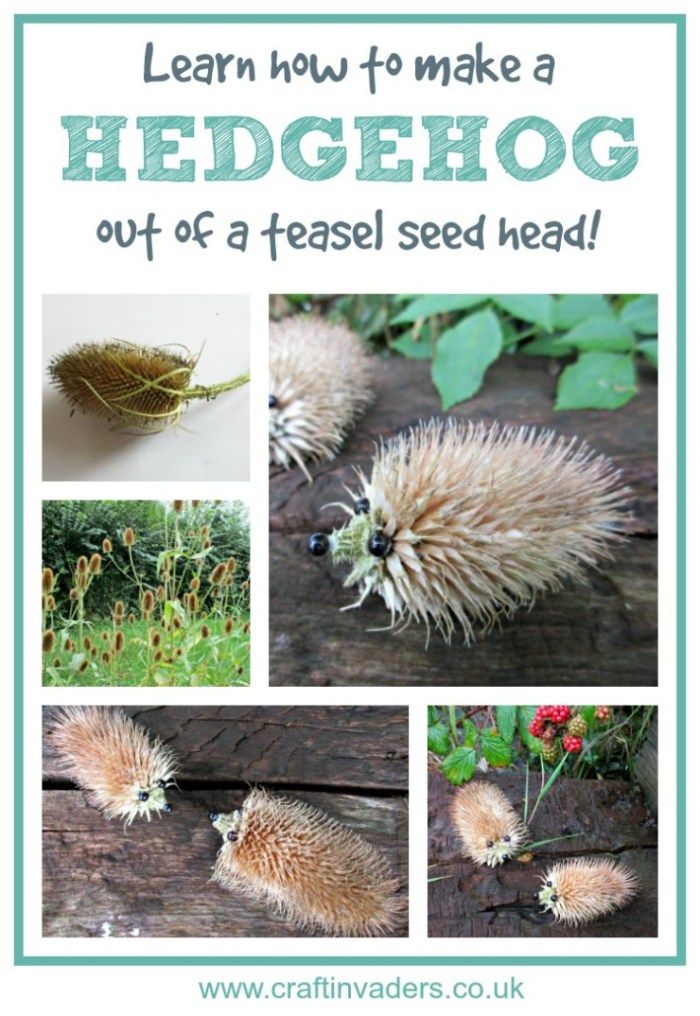

An alternative use is to make animals out of the seed-heads, including hedgehogs, but I think I will stick to the non-prickly knitted variety …

The name ‘teasel’ is variously spelled: teasle, teazel, teazle. I once played Sir Peter Teazle in our school play – once the torment of A-levels was over, the Upper Sixth was required to put on a show for the rest of the school and parents. (Heaven only knows why, in an all-girls school, The School for Scandal, a play with only four female characters was chosen …) I assume Sheridan chose the name to reflect the prickly character of the bad-tempered old man.

Teasels did not appear very often in art until the twentieth century, when the architecture of the seedheads seems to have become very appealing, especially to print-makers, but here are two older examples.

Caroline

Dear Professor Hedgehog, I have received a copy of the School for Scandal programme now, by email. It was performed on 16th July 1969. Would you like to see it? Jackie Long

LikeLike

Gosh, if you can send it by email? Thanks!

LikeLike

Delightful piece!

LikeLike