Part of my early morning routine (assuming I have the time to do anything except swallow my medication and dash out of the house) is to read the daily blog of the great and good Gentle Author: https://spitalfieldslife.com/. He posts every day without fail (don’t ask me how), usually on topics relating to the East End of London, but occasionally moving further afield. His posts are fascinating, full of information on the history, quirks and inhabitants of his patch.

A few weeks ago, as part of a sequence on ‘The Cries of London’, the collections of street vendors’ shouts advertising their wares as they moved around the city, he wrote on ‘Samuel Pepys’ Cries of London’, which included (among the more familiar subjects such as ‘hott codlings’ and ‘Waynfleet oysters’, a woman selling ropes of ‘white St Thomas onyons’.

‘Duh?’, I thought and reached for my great standby, John Brand’s Observations on Popular Antiquities, Chiefly Illustrating the Origin of our Vulgar Customs, Ceremonies and Superstitions, the 1813 edition, edited and expanded by Sir Henry Ellis (1777–1869), Keeper of Manuscripts at the British Museum, who according to his ODNB biography was later at the centre of terrible row about the Museum’s, and specifically the Library’s, purpose and accessibility, which led to the appointment of (later Sir) Anthony Panizzi.

Brand himself was born in 1744, and after the early death of his mother and the remarriage of his father, was raised in Gateshead by his aunt and uncle. Educated at Newcastle Grammar School, he was apprenticed to his uncle as a cordwainer (I never knew that a cordwainer only made shoes, and a cobbler only repaired them!?), and became a freeman of the guild in 1768. However, his schoolmaster, Hugh Moises, had continued to take an interest in him, and found patrons to send him to Lincoln College, Oxford, where he was ordained. Patronage also found him curacies in Northumberland, including a ‘perpetual’ one which he retained until his death, but the Duke of Northumberland caused him to move to London by making him joint rector of St Mary-at-Hill and St Mary Hubbard in the city, as well as the duke’s domestic chaplain.

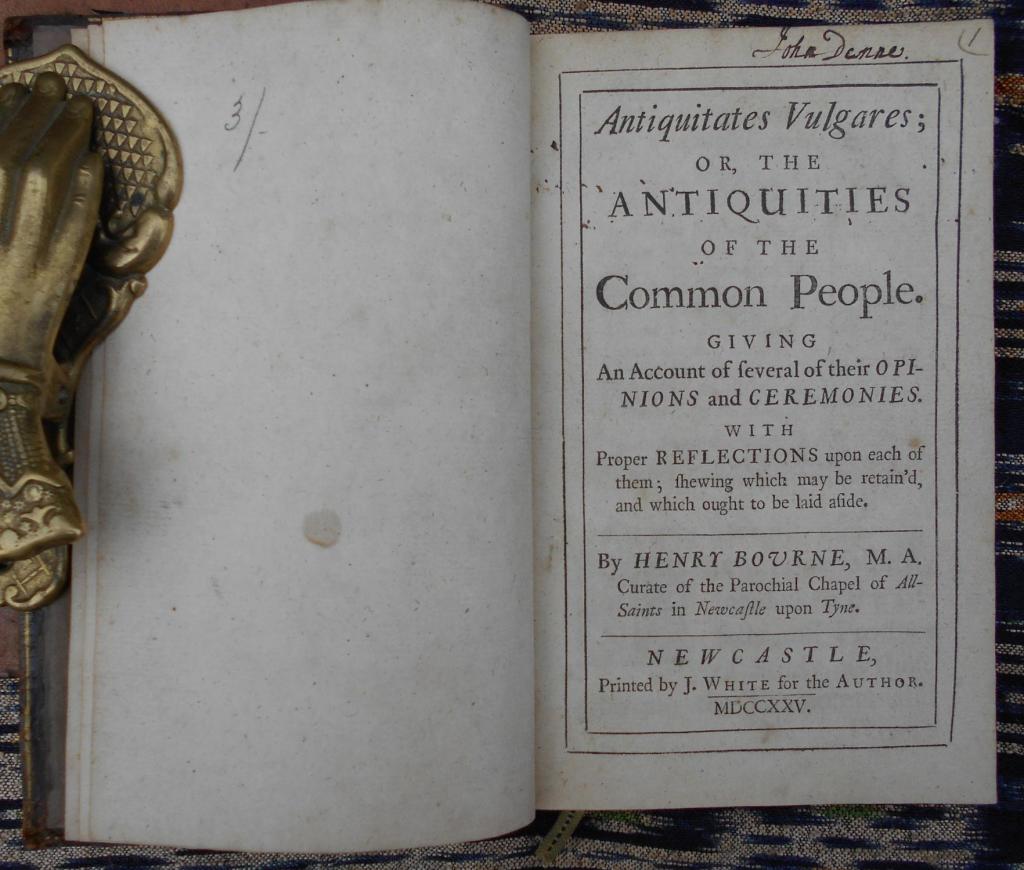

He had published Observations on Popular Antiquities before his move to London: it was not original but an expanded version of the Antiquitates Vulgares, or The antiquities of the common people, giving an account of their opinions and ceremonies of Henry Bourne (1694–1733), also of Newcastle, whose life – from humble origins to Christ’s College, Cambridge, to a curacy in Newcastle where he remained for the rest of his life, and also wrote a history of the city of Newcastle – Brand’s mirrored. Bourne’s Antiquitates was published in 1725: it was very successful, and copies were rare when Brand undertook to expand and reissue it, exactly as Sir Henry Ellis later did to Brand’s work.

Anyway, back to St Thomas and his onions. I had thought that his feast day was on 21 December, but in Christian communities in the Middle East and India (he was Apostle to the Indians, and is buried in Mylapore), it is 3 July. Ropes of onions would have been sold in the autumn in the streets of London, but the association with St Thomas appears to be a properly pagan one: these onions were used for divination.

St Thomas’s day itself is described by Brand as the day for ‘going a gooding’:

The custom of ‘Hagmena’ is described as a Franconian activity: ‘it is customary for the youth of both sexes to go from house to house, knocking at the doors, singing their Christmas Carols, and wishing a happy New Year. They get, in return, at the houses they stop at, pears, apples, nuts, and even money’. Brand continues: ‘The very observable word “Hagmena”, used on this occasion, is by some supposed of an antiquity prior to the introduction of the Christian Faith. Others deduce it from three French words run together [Homme est né, = Hogmanay] and signifying, “the man is born”. Others again derive it from two Greek words, signifying “the holy month” [αγια μηνη]’.

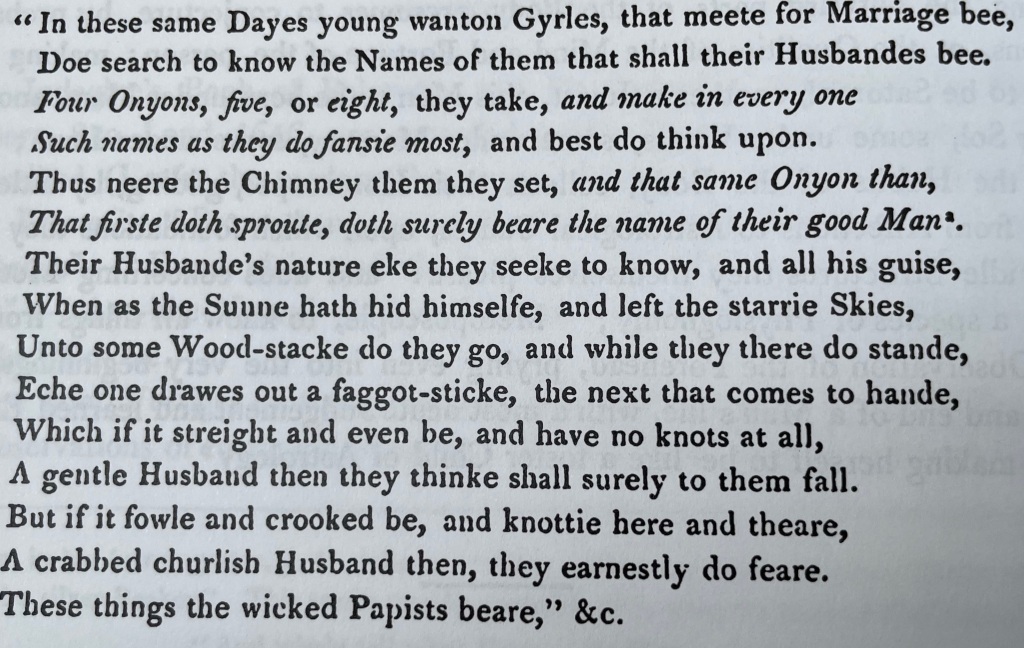

But in Volume 2, ‘Customs and Ceremonies’, there is a section on ‘Divination by Onions and Faggots in Advent’ (the faggots are wooden sticks or poles rather than meatballs). One of Brand’s sources is Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy (1621, with many subsequent editions). Citing the 1660 edition, Brand describes ‘”Cromnysmantia”, a kind of Divination with Onions laid on the altar at Christmas Eve, practised by Girls, to know when they shall be married, and how many Husbands they shall have’. He continues: ‘This appears also to have been a German custom. We have the following notice of it in Barnabe Googe’s Translation of Naogeorgus’s Popish Kingdom.’

Thomas Naogeorgus (or Kirchmeyer) (1508–63, born on St Thomas’s Day!), was a Protestant theologian and humanist, whose Regnum Papisticum, satirising Catholic superstitions, was published in Latin in 1553 and in German in 1555. Barnabe Googe (1540–94, spelling of first name and surname various), the English poet, translator and diplomat (he was a relative of William Cecil), called his translation The Popish Kingdome, or, Reigne of Antichrist. Sadly, there do not seem to be any surviving images of either gentleman.

Brand adds two further notes: one from the Catholic priest and exile Edmund Thomas Hill (1564–1644), who in his 1600 A Quartron of Reasons of Catholic Religion with as many Brief Reasons of Refusal (published in London in 1600, though with the deceptive place of publication as Antwerp), perhaps predictably blames the other side: ‘ … with the introduction of the Protestant Faith … were introduced your Gallegascones, your Scabilonians, your St Thomas Onions, your Ruffes, your Cuffes, and a thousand such new-devised Luciferian trinckets’.

Gallegascones are presumably galligaskins, the wide and floppy breeches of the period, as worn here by Charles I:

I can’t find out what Scabilonians are, but ruffs and cuffs are hardly (I would have thought) new-devised Luciferian trinkets? They were as popular among the Catholic upper classes of Europe as the Protestant. Here is but one example:

So why St Thomas’s onions among these fashionable items of the early seventeenth century? Ideas welcome! Brand’s last note is from A dialogue between Mistris Macquerella, a suburb bawd, Ms Scolopendra, a noted curtezan, and Mr Pimpinello an usher, &c. Pittifully bemoaning the tenour of the Act (now in force) against adultery and fornication, an anonymous satire of 1650, in which Mistris Macquerella (‘macquerelle’ being slang for a bawd at the time) remarks that ‘Some convenient well scituated Stall (wherein to sit and sell Time, Rue, and Rosemany, Apples, Garlike, and Saint Thomas Onions) will be a fit Palace for me to practice Pennance in.’

So perhaps the divination for a husband carried out using St Thomas’s onions has become an allusion to bawdy behaviour? However, this is not exactly confirmed by the expression on the onion-seller’s face in Pepys’s cutting …

Caroline

Fascinating, Caroline

LikeLike

I think that the Scabilonians relate to the ‘scavilones’ which in 1876 were defined as ‘Long drawers worn under the hose by men in Queen Elizabeth’s time’ (J. R. Planché Cycl. Costume 1876, I. 447): OED cites a reference in Holinshed to an individual coming into a room, ‘having put off hys nether stockes’ and ‘so bare foote and bare legged saue hys silke scauilones to the ankles’. Clearly extravagant and luxurious.

LikeLike

Thanks so much – I should have asked you if you knew!

LikeLike

While fascinating, I think you may be a bit wide of the mark here. ‘St Thomas’ here is simply a name for a type of onion, like a modern cultivar name, or a ‘Granny Smith’ apple. For centuries French growers brought onions in ropes over to England – the last has just about retired, I read recently – and would in more recent times ride around on their bicycles, with the ropes hanging all over them, selling them door to door. Here from the Society for Medieval History, is their explanation:

corruption of st Omer Onion [see Parkinsons paredisi] imported from france see London port Books] and hawked by the rope around the streets of London by women [street Cries]probably mainly in August and September.

https://soc.history.medieval.narkive.com/Xzsue9oa/st-thomas-onions

Not quite sure how you get from ‘St Omer’, to ‘St Thomas’, but perhaps one would need to know more about medieval pronunciation to follow it, and if Parkinson though it, I would trust his judgement.

Thank you, though, for the explanation of Hogmanay. As an anglophone now living in France, that makes a lot of sense. In times of low literacy, people just repeat what they hear, and then the few who can write tend to transcribe it literally.

Always enjoy your site, and the great blogs, they must take hours to do!!

LikeLike

Thanks so much for this, hugely interesting! I was brought up on the south coast and remember the French onion men very well. I must look at Parkinson. But the association with divination at the time of year still holds good, I think?

LikeLike

Oh, yes, I think it probably does, and I was fascinated by the story of girls putting the names on them and waiting for them to sprout! That has a ring of authenticity about it. I wasn’t trying to say you were wrong, just that there was an underlying explanation for the name and their sale, but the extrapolations seem very likely. Love this blog, I wish I had more time to read it, but you wonder where it all goes, don’t you? My background is plants, but I love history, social anthropology, and plant exploration too, and the links between plants and culture are endlessly fascinating.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for these kind words!

LikeLike